Rare Diseases

For each of the rare vascular diseases of the brain or eye linked to the CERVCO reference center, you will find below information documents concerning the characteristics of the disease and its management.

For each of the rare vascular diseases of the brain or eye linked to the CERVCO reference center, you will find below information documents concerning the characteristics of the disease and its management.

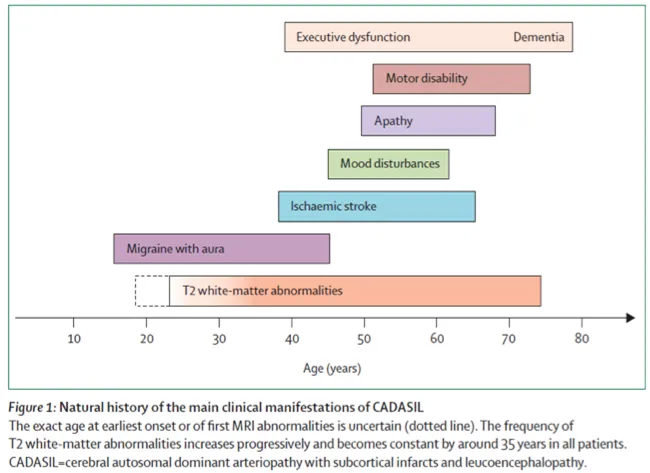

CADASIL is the acronym for « Cerebral Autosomal Dominant Arteriopathy-Subcortical Infarcts-Leukoencephalopathy”. It is a genetic disease with autosomal dominant transmission. The current clinical manifestations include migraine with aura starting between the ages of 20 and 40, cerebral infarcts usually occurring at about 50 years and cognitive deficits which become noticeable between the ages of 50 and 60 and gradually worsen with the development of dementia, motor difficulties and loss of balance in the terminal phase of the illness. Mood swings (depressive episodes, sometimes with mania or melancholia) are frequent. However, the development of the disease is extremely variable, with some patients showing only a few symptoms, which develop over time or with late onset while in other cases there is a rapid development of severe handicap.

MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) shows an increase signal in the white matter, small deep infarcts (lacunar infarcts) and sometimes-minor blinding. Certain neuroradiological features are highly suggestive of the disease, in particular the presence of hyper signals in the anterior poles of the temporal lobes of the brain on T2 or FLAIR sequences.

The gene responsible (Notch3) is on the short arm of chromosome 19. The protein encoded by the Notch3 gene is a membrane receptor expressed in the smooth muscle cells within the wall of small blood vessels throughout the body and, in particular, in the brain. Gene mutations cause this protein to accumulate in the vessel wall. The diagnosis, which may be strongly suspected from clinical and neuroradiological data is confirmed by the search for mutations of the Notch 3 gene using a genetic test that provides a diagnosis in 100% of cases.

No specific treatment of the disease has been assessed to date but treatment of the symptoms and psychological care are always necessary.

This document has been produced by ORPHANET working jointly with the CADASIL France association and CERVCO.

Source: CADASIL, Encyclopédie Orphanet Grand Public, avril 2008

http://www.orpha.net/data/patho/Pub/fr/CADASIL-FRfrPub1001v01.pdf

CADASIL is a genetic disease affecting the small blood vessels in the brain. It leads to poor blood supply to certain areas of the brain, causing symptoms that vary greatly from one patient to another. The commonest signs of the disease, which appear in adulthood, are migraine, psychic disorders and stroke which can affect language, memory, vision etc.

The term CADASIL was suggested in 1993 by French researchers as the name of the disease. It is an acronym which, in English, stands for « Cerebral Autosomal Dominant Arteriopathy with Subcortical Infarcts and Leukoencephalopathy ».

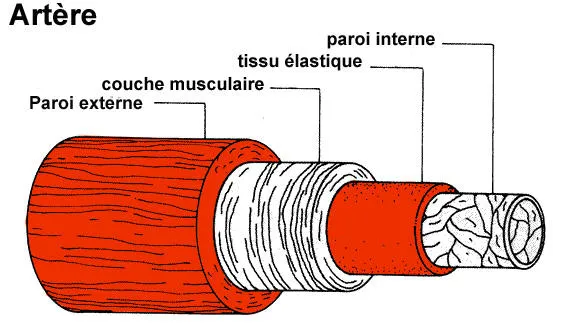

The term « cerebral arteriopathy » means that the arteries in the brain are affected. These are the vessels which carry the blood to all the organs in the body.

« Autosomal dominant » describes the way in which the disease is passed from one generation to the next, since this is a hereditary illness.

The term « infarct » means the sudden cessation of blood circulation in one part of the body which, in the case of CADASIL, is the « sub-cortex », one of the regions in the brain.

Finally, the word « leukoencephalopathy » refers to lesions in the brain caused by the disease (see below).

The prevalence of CADASIL (i.e. the number of people affected within a population at any given moment) is not known exactly but it is estimated to be 1 in 24,000. However, this prevalence is probably an underestimation.

The disease affects as many men as women. The symptoms appear in adulthood, usually between the ages of 30 and 40.

Although initially described in Europe, CADASIL has since been observed in populations from very different backgrounds, all over the world.

The disease is caused by an abnormality (a mutation) in a gene called NOTCH3.

This is an important gene during foetal development, controlling blood vessel formation and, to be more precise, the formation of the muscle layer which is a part of the arteries.

Because of the abnormality in the Notch3 gene, the muscle layer in the arteries is of poor quality and it is gradually damaged. The walls of the arteries become less elastic and blood circulation is more difficult.

Although it affects the small arteries in all the organs of the body, the consequences of the disease are only apparent in the brain, leading to the neurological problems described below.

Certain areas of the brain, which are irrigated by small arteries, are deprived of a blood supply and, therefore, of oxygen by the abnormality in the small arteries. This is what we call an « infarct ». Oxygen is essential for cell function and survival and the repetition of small infarcts in part of the brain cause the initial symptoms and gradually cause them to worsen.

Figure 1

An artery is a sort of flexible tube consisting of several concentric layers or « tunics ». One of them is a solid, elastic layer of muscle that maintains the diameterof the artery and enables the blood to circulate. The Notch3 gene plays a part in the development of this muscle layer.

(http://www.ulb.ac.be/erasme/edu/fcc/hypertension/images/sch_artere_400.gif)

No, CADASIL is not a contagious disease; it is a hereditary genetic disease.

The disease is caused by an abnormality in the arteries and is present at birth but the first symptoms do not generally appear until adulthood (around 30 or 40 years of age). The symptoms vary greatly from one person to another, even within the same family (even though they all have the same genetic abnormality). Not everybody has all the signs described below. Likewise, the severity of the symptoms and, therefore, of the handicap resulting from the disease is unpredictable and very variable.

Attacks of migraine with aura are frequent with this disease and are often the first symptom. Migraines are severe headaches (usually on one side of the head only), sometimes accompanied by nausea, vomiting and an inability to tolerate noise and light (patients need to lie in a silent, dark room). These headaches can occur on their own but they are often preceded by abnormal feelings called « aura ». Migraines with aura affect approximately one patient in four. The frequency of the attacks of migraine with aura varies greatly, ranging from two per week to one every three or four years.

The signs preceding a migraine, the « auras », differ from one patient to another. They usually last for 20 to 30 minutes, followed by the headache. They usually affect vision and may consist of dazzling « floaters » passing across the field of vision, coloured spots, the sudden appearance of a bright light in the centre of the field of vision (scintillating scotoma) or, more uncommonly, blurred vision or loss of vision in one half of the field of vision (hemianopia).

Other signs may affect the body’s sensitivity with numbness, tingling, tickling, muscle weakness or even paralysis on one side of the body. These sensations can sometimes spread throughout the body.

Speech difficulties may also appear, often in the form of difficulty in finding words (aphasia) or in pronouncing them. The aura can also consist of a feeling of depression, anxiety or agitation.

Patients can also suffer from migraine without aura. However, this type of migraine is not more frequent in CADASIL patients than in the general population.

Migraines attacks can be extremely painful, sometimes unbearable, and can last for several hours or even for several days. In some cases, the attack is so severe that it requires hospitalisation for the patient.

Stroke occur during this disease when an area of the brain is suddenly deprived of blood supply (infarction or ischaemia). Repeated brain infarctions are the most frequent complication of the disease, affecting more than three out of four patients. They usually occur between the ages of 40 and 50.

They can cause various symptoms, all of which occur suddenly e.g. paralysis of one side of the body (hemiplegia) or loss of feeling in one part of the body, speech difficulties, loss of balance or lack of coordination in movements.

These difficulties may regress in less than 24 hours but they may also become permanent as the disease develops. When they are « temporary », they are called transient ischemic attacks (TIA); if the difficulties are irreversible, they are called brain infarction.

Mood alterations occur in approximately 20% of cases, either after a brain infarction or at any time during the progress of the disease. Certain patients show signs of major depression and a loss of motivation and interest in their work, leisure activities, plans for the future etc. (apathy). In rare cases, phases of depression alternate with phases of hyperactivity (excessive expenses, unusual remarks or behaviour patterns, a range of excesses etc.). They are described as suffering from bipolar disorders. The existence of these psychiatric disorders may lead to diagnostic errors, especially when they are the first signs of the disease.

So-called « cognitive » difficulties may also occur, from the onset of the disease. However, they do not become significant until the ages of 50 to 60. They consist of difficulties with concentration, a shortened attention span, or memory difficulties and vary in severity. People who are affected in this way often find it difficult to organise activity, plan something or take initiative. They also find it difficult to adapt to new situations and manage the changes that occur in everyday life. This affects executive functions (organisation, planning) and leads to a loss of mental flexibility.

With age, the intellectual decline may become worse, either gradually or in stages (sudden, major worsening). Attention and memory difficulties increase, as does the loss of initiative. The worsening of these difficulties may lead to a loss of independence, a condition referred to as dementia or dementia syndrome.

Dementia is observed in one-third of all patients but its frequency increases with age. After the age of 60, some 60% of patients suffer from dementia, possibly associated with other signs such as difficulties with walking, urinary incontinence and, in certain cases, difficulties swallowing.

In less than 10% of cases, patients also have epileptic seizure of various types (movements or convulsions including muscle spasm, tremor and stiffness), sensory disturbance (tingling, numbness, auditory or visual hallucinations i.e. hearing sounds or seeing things that are not there, etc.), psychic difficulties (panic attacks or panic-based fear, memory loss, confusion, loss of consciousness, absences _sudden loss of contact with the environment of which the patient has no memories afterwards, or excessive salivation, urinary incontinence etc. The fits can affect the entire body (general seizure) or, more often, a limited part or one-half of the body (partial seizure).

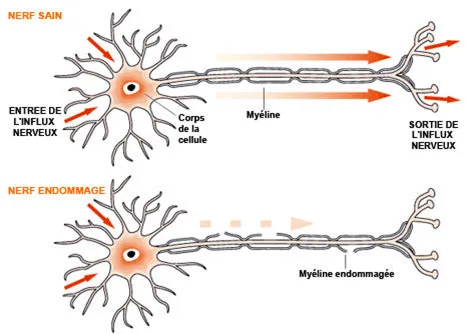

The loss of oxygen because of poor blood supply damage certain areas of the brain, creating lesions. After a few minutes without a blood supply, certain cells are permanently destroyed. To be more precise, it is the « white matter » in the brain which suffers most often during this disease. This is why we use the term « leukoencephalopathy » (« leuko » means « white » in Greek). The white matter consists of bundles of « cables » known as axons, which are extensions of the nerve cells, or neurones (figure 2). These « cables » are covered in an insulating sheath called « myelin », similar to the insulation that covers electrical wires.

Myelin helps to transmit the nerve message that operates in the brain. In people with CADASIL who suffer repeated minor infarcts or micro-haemorrhages, the myelin is altered or even destroyed (this is called « demyelination) in certain areas of the brain. The alteration damages or prevents the transmission of nerve messages in the brain and this is what causes a gradual loss of independence.

Figure 2

The nerve cells are extended by « axons » covered with a white myelin sheath. It is the axons, which « wire » the brain, that make up the white matter in which lesions are formed during CADASIL. (http://www.medisite.fr/medisite/Aquelles-lesions-anatomiques.html)

Breaks in the blood circulation seem to be increasingly frequent and severe as the disease progresses, which explain the gradual build-up of cerebral lesions and the worsening of symptoms. Once a lesion forms in the brain, it is permanent but other circuits may be built up to compensate for this loss, enabling the person to recover the functions lost. However, such an ability decreases gradually and the difficulties then become increasingly obvious.

The reason for which some people develop a more severe form of the disease is unknown.

In most cases, the onset of the disease is marked by the appearance of migraine with or without aura after the age of 30 then the occurrence of stroke some ten or twenty years later and by the gradual onset of cognitive difficulties (problems with concentration, memory loss etc.) and difficulties with balance and walking at about the age of 60. After 60 years of age, the loss of independence and intellectual decline can be significant.

However, the severity of the disease varies greatly from one person to another, even within the same family. The disease develops more or less quickly. Some patients are seriously handicapped very early on, at about the age of 40, while others do not have the first symptoms of the disease until they have passed the age of 70.

Diagnosis of the disease is initially based on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). This is a painless examination in which the patient is placed in a device that produces a magnetic field. This then gives precise images of the brain. MRI diagnosis is completed by genetic testing.

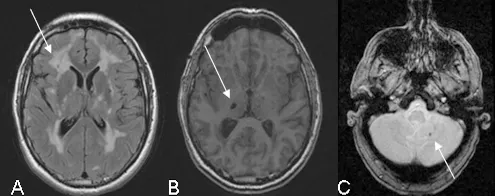

In the case of CADASIL, the MRI detects lesions that are characteristic of the disease in the white cerebral matter (figure 3). The lesions usually appear between the ages of 20 and 35 but they may be present for many years without causing any symptoms. After the age of 35, all carriers of the abnormal Notch3 gene have abnormalities visible on an MRI scan and indicative of CADASIL, whether or not they have any symptoms. The number and extent of the abnormalities detected by an MRI scan increase with age.

In very rare cases, a skin biopsy is carried out to help in the confirmation of the diagnosis. This is a small sample taken under local anaesthetic, used to study the condition of the small blood vessels in the skin. Even if CADASIL is not causing any neurological symptoms, abnormalities in small arteries are visible all over the body, especially in the skin.

The CADASIL diagnosis is confirmed by taking a blood sample and looking for abnormalities in the Notch3 gene. This search requires specific management and follow-up.

Strokes are relatively common in the population as a whole and more particularly among the elderly, diabetics, hypertensive, smokers and people with high cholesterol. CADASIL is not therefore discussed when the first symptoms of stroke arise. However, the detection of typical lesions in the brain through the use of MRI scanning can alert the practitioner to the existence of a specific disease. When other cases have already been diagnosed in the family, it is easier to diagnose CADASIL but MRI scanning and genetic testing remain necessary to confirm the diagnosis since the neurological symptoms may be due to other diseases. Among the « similar » diseases are multiple sclerosis progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy, cerebral amyloid angiopathy and Alzheimer’s disease

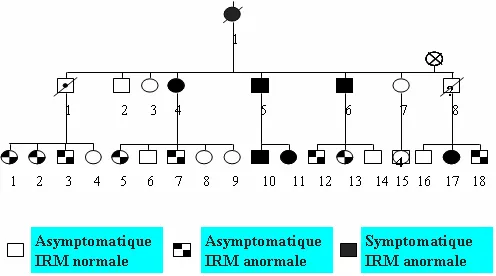

CADASIL is a hereditary familial disease. Its transmission is autosomal dominant, which means that a person already affected by the disease has a 1 in 2 chance of passing the abnormal gene on to his or her children (Figure 4). All the people who have inherited the abnormal gene will develop symptoms of the disease at some time or another. However, the severity may vary considerably from one person to another, even within the same family.

In a few known exceptional cases, the mutation of the Notch3 gene has occurred « randomly » (« de novo mutation »), without having been transmitted by one of the parents.

It is possible to do a screening test before the appearance of any symptoms of the disease, in the members of a patient’s family (presymptomatic testing). The test will show whether a person has the genetic abnormality and, therefore, whether he or she will develop the disease one day.

However, in a person with no sign of the disease, genetic testing will only be offered as part of a specialist consultation and precise medical and psychological management. No test will be carried out on children and young adults under the age of 18 if they are symptom-free.

After examination by a neurologist, who will give the patient information about CADASIL, the patient will have an interview with a psychologist and a consultation with a geneticist.

Since the decision on whether or not to use this presymptomatic test is a complex and difficult one, the person concerned must be given the best possible information and support. The psychologist will assess the patient’s psychological condition, his or her current thinking and questions about the disease, and his or her ability to deal with a difficult diagnosis. The geneticist will explain the test and the meaning of the results.

If the person decides to have the test, a cooling-off period of one or two months is required before the blood test. It is possible to change one’s mind at any time and choose not to know the result. Medical and psychological support is always proposed once the results become available (approximately 3 months after the blood test), whether positive or negative.

In families in which the disease takes a particularly severe form, people do sometimes seek prenatal diagnosis.

The aim of prenatal diagnosis is to determine, during the pregnancy, whether the future child will carry the mutation and therefore develop the disease when an adult (in this case, the parents can request a termination of pregnancy). A prenatal diagnosis is done by sampling the fluid in which the foetus lives (the procedure is called an amniocentesis) or by removing a fragment of placenta (sampling of chorionic villus).

It is also possible to undertake a pre-implant diagnosis (PID), which consists of seeking the genetic abnormality responsible for the disease in the embryos obtained by in vitro fertilisation (IVF). This technique allows the practitioner to select the embryos which are free of the genetic abnormality before implanting them in the uterus, avoiding the parental trauma of a late-term interruption of pregnancy.

Although both prenatal diagnosis and PID are technically feasible, it is nevertheless exceptional to have recourse to them. CADASIL is a disease which only becomes apparent in adulthood and its severity varies from one patient to another, even within a single family. This means that, even is some members of the family are or have been severely affected when they were relatively young, there is nothing to indicate that future children will, if they carry the abnormal gene, have severe symptoms as early in life.

Such an approach to the disease is a very long process, requiring support from the entire care team.

At present, there is no treatment that can cure the disease or prevent its onset. However, it is possible to treat the symptoms as they occur, to improve the patient’s quality of life. Research is underway to identify treatments that might delay the onset of the disease.

Traditional analgesics (pain relief) such as paracetamol, ibuprofen and aspirin (non-steroidal anti-inflammatories or NSAIDs) are used to treat migraine. However, they are often insufficient.

The medicines most commonly used to treat migraine, the so-called « vasoconstrictors or triptans », are not recommended for patients with CADASIL because they cause the blood vessels to contract and may therefore reduce the blood flow to the brain.

Aspirin is traditionally used as preventive treatment after the first stroke has occurred. Aspirin increases the fluidity of the blood and limits the formation of the clots that cause most strokes occurring in the population at large. However, in CADASIL patients, the beneficial effects of aspirin have not been clearly demonstrated. If in doubt, most doctors will nevertheless prescribe this treatment, varying the dose depending on the patient, unless there is some contra-indication (stomach ulcer, allergy etc.).

Psychiatric disorders which may produce signs of depression or bipolar disease can be treated with antidepressants but sometimes they may be inadequate or totally ineffective.

After a stroke, physiotherapy is essential to deal with the possible resultant motor disorders (walking, balance etc.). If there are speech difficulties, speech therapy is recommended. If the stroke leaves significant relapse (e.g. paralysis), psychomotricity and ergo therapy can assist the patient by helping him or her to manage his or her handicap and accepting body image so that he or she can develop their maximum potential within their specific environment.

As to treatment for cognitive difficulties, it can include participation in appropriate groups (with other sufferers, for example) to stimulate the patient, avoid isolation and limit the feeling of being a burden on the family or carriers.

If there is a loss of independence (intellectual impairment, behavioural difficulties, significant motor difficulties), the patient may require specialist home care or may even need hospitalisation in a specialist centre where he or she will receive assistance with everyday life (hygiene, diet).

Psychological support is often essential, at every stage of the disease, for both patient and family.

Receiving the diagnosis is a difficult time, often met with a combination of injustice, powerlessness and despair because this is not a treatable disease and it is therefore impossible to foresee how it will develop. In the more or less long term, however, it will cause physical and mental decline.

Moreover, since it is a familial disease, the fear of transmitting (or having transmitted) it to one’s children is often strong and associated with a feeling of guilt. Psychological support can help patients to accept the situation more easily and even manage the anxiety linked to the disease more effectively.

For the family (siblings, children), psychological support is important and is helping them reach a decision on whether to ask for a screening test or live with uncertainty without giving up any of their plans for the future. For people who know they are affected but have not yet developed any symptoms, or for the members of the family who do not know whether or not they carry the abnormal gene, it is « natural » to worry at the least neurological sign (headache, pins and needles in a limb etc.). However, CADASIL is not necessarily the cause and two people with the same genetic abnormality will not necessarily have the same symptoms. Nor with the disease develop in the same way. The assistance of a psychologist, in addition to various relaxation methods, can be useful in calming anxiety and fear.

There are no particular recommendations but it is preferable to have a healthy lifestyle and to avoid smoking (because it increases the stroke risk). It is also recommended to have regular blood pressure checks.

Generally speaking, to avoid taking unnecessary risks, hormone replacement therapy is only continued at menopause if it brings real benefits (as treatment for hot flushes etc.) and then only for a limited time. As to contraception, a pill containing only progesterone (and without oestrogen) may be preferable to the usual contraceptive pill.

CADASIL patients are monitored through specialist consultations in hospital neurology departments. In France, there is one reference centre for rare vascular diseases of the central nervous system (details can be found on the following website www.orpha.net). The frequency of consultations and tests will be decided by the medical team.

Certain symptoms should nevertheless ring warning bells in the patient and his family or carers and cause them to seek an urgent appointment. A stroke may lead to difficulties with vision or speech, sudden difficulty in moving a limb (for example, it may become difficult to write), difficulty in coordinating movements etc. Likewise, if there are severe headaches with or without aura, or epileptic seizures, an appointment with the doctor should be sought without delay.

In case of emergency, it is important to tell the doctors of the CADASIL diagnosis so that certain treatments or tests can be avoided. For example, anticlotting medication, which is sometimes given after a stroke, is strongly inadvisable for CADASIL patients because of the risk of bleeding in the brain. Likewise, cerebral conventional angiographies (examinations which show blood flow through the arteries in the brain) should be avoided because they may cause a migraine which, in some cases, is very serious. Finally, you must tell the medical teams about current medication and the corresponding doses. This is a precaution, avoiding the combination of incompatible medication and any risk of overdose.

To date, nothing has been shown to be effective in preventing the onset or signs of CADASIL.

Suffering from a disease that develops and that, sooner or later, causes physical and mental decline is extremely difficult, even though it is impossible to forecast the severity of the handicap and the speed with which the disease will develop since they vary from one person to another. The neurological problems eventually impair essential functions such as walking or speaking and are, therefore, very disabling. The patient’s condition may remain stable for some time but the development of the disease during active life may require the patient to give up work or, at the very least, to redirect or reorganise his or her working life. Moreover, if a stroke occurs, hospitalisation and often lengthy physiotherapy are essential if the patient is to recover as many of his or her faculties as possible.

For people who already have symptoms and for those who know (or think) that they are carrying the disease, the feeling of living under a permanent threat can be difficult to manage and cause immense anxiety. The unforeseeable nature of the disease is particularly difficult to accept.

When the disease is very far advanced, the patient gradually loses his or her independence and becomes incapable of undertaking everyday tasks (washing, eating etc.). For the patient’s family or carers, mood disturbances and psychological disorders sometimes accompanied by motor difficulties and incontinence are very difficult to cope with. They often lead to social isolation since friends and, in some cases, family do not always understand the changes in the patient’s behaviour. Once the patient become incapable of taking decisions, he or she may have to be placed under guardianship. The guardian, who is often a member of the family, must take responsibility for financial management in the patient’s place.

At an advanced stage of the illness, to lighten the burden of maintaining the patient at home, external agencies (home nurses, home carers, cleaning ladies or placement in a specialist home) can be arranged. This « rest » periods are essential for the family.

It is possible to have children when affected by CADASIL or when one is a carrier of the genetic anomaly responsible for the disease. Pregnancy does not appear to increase the risk of stroke; nor does it cause symptoms in women who have never previously had any signs of the disease.

However, during the month following the birth, the risk of severe migraine with aura would seem to be increased. It is therefore important to discuss any desire for pregnancy with one’s doctor or let him or her know if pregnant. This will enable the practitioner to assess the risks for the woman and the future baby and provide the appropriate follow-up.

The aim of research is to pinpoint the mechanisms through which the anomaly in the Notch3 gene leads to lesions in cerebral arteries. To do this, mice have been produced with an anomaly on the Notch3 gene. The factors determining the severity of the symptoms and the progress of the disease, both of which vary from one patient to another, are also being studied at the present time.

Therapeutic studies are envisaged in the clinical context, in particular to assess the efficacy of vasodilator or neuroprotector medication.

The research is being carried out by various teams worldwide.

CADASIL (Cerebral Autosomal Dominant Arteriopathy-Subcortical Infarcts-Leukoencephalopathy) is a hereditary autosomal dominant disease affecting all the small cerebral arteries. It causes subcortical infarcts and damages the white matter (leukoencephalopathy) and it is due to various mutations of the Notch3 gene situated on chromosome 19.

Initially described in Europe, the disease has now been observed in families with very different ethnic backgrounds, on all continents. At present, there are more than four hundred families in Europe. There has not yet been any real epidemiological study of CADASIL in France. The authors of a study carried out in the West of Scotland in 2002 listed 22 patients with CADASIL from seven families out of a population of 1,418,990. Considering the relatives of these patients, who risk being carriers of the mutated gene, the researchers estimated the prevalence to be 4.15/100,000 inhabitants. It is, though, likely that the frequency of the disease is as yet underestimated.

The initial clinical signs, which are observed in 20% to 30% of patients, are the onset of migraine with aura starting between the ages of 20 and 40. Cerebral infarcts (ischemic strokes) are observed in 70% to 80% of patients with onset usually around the age of 50. There are also cognitive disorders (difficulties with concentration and attention, memory loss), to a greater or lesser extent. These difficulties occur very early in the development of the disease but do not become significant until the 50 to 60 years age span. These cognitive difficulties may lead to a change in social life and, eventually, to almost constant dementia in the terminal phase of the illness, combined with difficulties in walking and balance. In 10% to 20% of cases, there are also psychiatric disorders and, in 5% to 10% of patients, there are epileptic seizures.

Migraines with aura (i.e. migraines accompanied by neurological signs) are reported by one in four patients The frequency of the migraines is extremely variable, ranging from twice a week to one every 3 or 4 years. Symptoms of the aura are, in order of frequency, visual, sensory, aphasic or motor. A visual aura manifests itself in various forms, most frequently as a scintillating scotoma and less often as blurring of vision or as a homonymous lateral hemianopsia. Speech disorders during attacks of migraine with aura can often be summarised as difficulties in expressing oneself, with reduced verbal fluency.

More than one-half of patients suffer migraine with atypical aura i.e. sudden-onset migraines with aura, « basilary » migraine or « hemiplegic » migraine. In a few cases, the migraines may be extremely severe such as those seen with familial hemiplegic migraine. They produce episodes of confusion, lack of vigilance, coma and hyperthermia (possibly lasting for several hours or several days).

Some 70% to 85% of patients report the occurrence of an ischemic event which can be a neurological deficiencyof sudden onset resolving in less than 24 hours (TLA transient ischaemic attack) or a permanent neurological deficiency. In most cases these signs indicate a minor stroke resulting in traditional signs (lacunar syndrome caused by the occlusion of a small artery: pure sensory deficit, pure motor deficit, or sensori-motor deficit of one side of the body or ataxic hermiparesis). These cerebral infarcts can occur in the absence of any of the usual vascular risk factors (arterial hypertension, diabetes, or hypercholesterolemia).

Mood disturbance are observed in one in five patients. They may be early (up to 10% of patients), sometimes inuagural and lead to an error or delay in diagnosis. Some patients describe symptoms of severe depression suggesting melancholia, alternating, in a few cases, with episodes of mania (this can lead to the presumptive diagnosis of bipolar disorder). Apathy (loss of motivation) is a frequent sign of the disease, depending on the location of the brain lesions. It is not always secondary to depression.

Cognitive disorders (difficulties with executive functions, attention and memory) are extremely frequent but of variable severity during the course of the illness. Alteration of the executive functions (planning, anticipation, adjustment, self-correction and mental flexibility) is the earliest symptom most frequently observed and it can be almost imperceptible for many years. Damage to the executive functions is frequently associated with attention and concentration disorders. Gradually, with age, the decline becomes more acute with the onset of apathy, often the most observable feature, and deficiencies in motor functions (tasks such as drawing or writing done using external resources), suggestive of diffuse cerebral damage. However, there is very rarely any severe aphasia (language difficulties), apraxia (difficulties with voluntary behaviour) or agnosia (difficulty with the recognition of objects, people or places with visual difficulties), all features frequently observed in Alzheimer’s disease. Semantic memory (linked to knowledge) and recognition are often maintained. Cognitive decline commonly appears gradually, often in the absence of any ischaemic events. This development may therefore suggest a degenerative disease. Sometimes, the patient suddenly worsens, in stages.

Dementia (cognitive difficulties that affect the patient’s everyday life and lead to a loss of independence) is observed in one-third of patients, especially after the age of 60. Its frequency increases with age and approximately 60% of patients over the age of 60 have dementia. It is often associated with other signs of the gravity of the disease e.g. difficulty with walking, urinary incontinence and, sometimes, a pseudo-bulbar palsy (difficult swallowing, spasmodic laughter or crying).

Despite the diffuse damage to small arteries in all organs, the clinical manifestations of the disease are only neurological and restricted to the brain.

The typical progression of the disease begins with the onset of migraine with aura when the patient is in his 30’s followed by transient or constituted ischaemic cerebral events a decade later and the gradual onset of cognitive difficulty, problems with balance and walking as the patient approaches the age of sixty. Loss of independence with motor and cognitive handicaps is frequent after the age of 60 (Figure 1)

This profile is not constant because of significant variability in the course of the disease, sometimes between several members of the same family (i.e. having the same genetic abnormality). In some cases, the disease can produce an early handicap at age of 40.Conversely, in other cases, the first signs of the disease may not appear until age of 70.

Figure1: A summary of the natural history of the disease

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is essential for the diagnosis of this disease. Abnormal MRI signals (abnormalities in the white matter of the brain) are sometimes detected before the onset of the first symptoms of disease. These abnormalities appear between the ages of 20 and 35 and can therefore remain inconsistent in this age group. On the other hand, after the age of 35, all the carriers of the mutated gene have MRI abnormalities suggestive of the disease, whether or not they have any symptoms. The total absence of MRI abnormalities after the age of 35 should cast doubt on the diagnosis.

Several types of abnormality may be observed (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Illustration of the MRI abnormalities detected on the following sequences: FLAIR (A), T1 (B) and gradient echo (C)

White-matter hypersignals (A) is constant when major symptoms of the disease are present. They are observed on T2 weighted sequences which show extensive hyper intense areas within the white matter of the brain associated with more focal abnormalities within the deep grey nuclei, thalamus and brain stem. The extent of white matter hypersignals is variable and increases with age. In patients under the age of 40, signal anomalies are usually punctiforms or nodular and are symmetrically distributed. Gradually, as the disease develops, hypersignals become confluent and extend to the entire white matter. The presence of these signal anomalies in the anterior temporal lobes (more than 2 out of 3 patients) is very important from the diagnostic point of view because of their great specificity. They are usually not seen in cerebral arterial diseases caused by hypertension or diabetes.

Lacunar infarcts (B) are detected on T1 weighted images in the form of limited zones with hypointense signal. They are punctiform or wider depending on the cavity forming as a secondary feature after a minor infarct. These lesions are observed in approximately two out of every three patients with abnormalities in the white matter of the brain. They are present within the white matter, deep grey nuclei and brain stem. The total volume of these lesions correlates strongly with the clinical severity of the disease.

Micro bleeds (C) are seen in one out of three patients, on average, using gradient echo sequences or (T2* sequences) since they are very sensitive to the accumulation of haemoglobin by-products in cerebral tissue. The bleeds do not usually produce any specific signs but their presence seems, in most cases, to be associated with greater damage to the vascular wall and greater severity of the disease.

CADASIL is a hereditary familial disease. The mode of transmission is autosomal dominant (found with the same frequency in both male and female patients, 50% of children born to a person with the disease have the genetic abnormality) (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Family tree showing the autosomal dominant transmission and the results of the MRI scan.

The diagnosis should be discussed with patients who have symmetrical lesions in the white matter of the brain and a clinical history of migraine with aura, TIA or brain infarction, mood alternations or cognitive difficulties of unexplained origin.

It is essential to question patients and seek clinical histories in other members of the family suggestive of the disease. A history of multiple sclerosis (an incorrect diagnosis of multiple sclerosis is sometimes made for young patients after a first clinical event), cerebral vascular events or gradual-onset dementia with motor deficit in relatives should point to a family history of cerebral small vessels disease. However, the total absence of any family history should not lead to the diagnosis being discarded because of the possibility of a new mutation in the gene responsible, causing new, sporadic cases.

The presence on an MRI showing T2 or FLAIR hypersignal, with symmetrical distribution in the cerebral white matter, especially in the anterior temporal lobes increases the likelihood of diagnosis (CADASIL) because of the specific nature of these signs.

Testing for other causes of damage to the small cerebral arteries (standard blood test, search for an inflammatory syndrome, search for vascular risk factors with tests for hypercholesterolemia, homocysteinaemia or fasting glucose, or ultrasound investigations of cervical and intracranial arteries) is usually negative.

If there is a strong suspicion of the diagnosis, a conventional angiography should be avoided because of the risk of severe neurological symptoms (severe headache, migraine with marked aura) which can, in some cases, be serious. This examination is usually normal, although it may sometimes show narrowing of the small arteries. An MRI scan is preferable if seeking to investigate the state of the medium and large arteries.

To confirm the diagnosis, genetic testing must always be carried out. The gene involved is the Notch3 gene, situated on the short arm of chromosome 19. It consists of 33 exons including 23 exons (2 to 24) which encode for EFG-like motifs with six cysteine residues. To date, all the mutations responsible for the disease have been located within these exons (exons 2 to 24). The mutations are highly stereotypical and all of them lead to the addition or loss of one cysteine in one of the EGF-like motifs. The presence of a mutation of this type confirms diagnosis of the disease beyond all doubt. Within the French population, the mutation lies within exons 3 or 4 of the Notch3 gene in 70% of cases while in 90% to 95% of cases, the mutation is located in one of the following 12 exons: 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 11, 12, 18, 19 or 20. In the absence of any known mutation in the patient’s family, exons 3 and 4 (70% sensitivity) are tested first, followed by exons 2, 5, 6, 7, 8, 11, 12, 18, 19 or 20 (95% sensitivity). If there are very strong pointers to the diagnosis (hence the importance of sending the clinical data and MRI scan) and if the previous analysis has been negative, screening can be extended to the last mutated exons in the gene in a very small number of CADASIL patients. The sensitivity of the screening of 23 exons encoding for the EGF areas in the Notch3 gene is estimated to be close to 100 %.

The diagnosis can rarely be made by a skin biopsy (punch biopsy) which shows the status of small vessels. There are two possible approaches – a study of the vessels under an electron microscope showing the accumulation that is characteristic of the disease within the wall of small vessels, known as GOM (granula osmiophilic material), or a study using an anti-Notch3 antibody which, under the microscope, highlights the accumulation of Notch3 protein within the vascular wall. Both of these methods are highly sensitive but technically fairly difficult to use. At present, these tests are carried out less and less frequently because molecular testing has become easier.

Genetic diagnosis is possible before symptoms of the disease appear, in the other members of an affected family. However, genetic testing is only carried out on healthy subjects with no clinical signs of the disease who have not had any previous test within the setting of a specialist multidisciplinary consultation. After a neurological assessment (neurologist), a psychological evaluation (interview with a psychologist) and a genetic consultation (geneticist), the patient’s request is assessed jointly by all the practitioners and a cooling-off period of several weeks is suggested before any blood test. The patient may request not to be informed of the results of the test throughout the procedure, until the final results are ready. Clinical and psychological follow-up are always proposed once the results have been given.

No genetic testing is currently carried out on minors who are symptom-free.

The symptoms of the disease are mainly produced by the lesions occurring within the brain as the disease progresses. The lesions observed in the white matter correspond to demyelination (loss of myelin sheaths which are manufactured by the oligodendrocytes in the white matter) and to a loss of axons in the brain’s neurons. These lesions are associated with minor infarcts occurring mainly deep inside the brain as a result of an interruption in the blood flow to an area supplied by a small artery. The infarcts can leave a small cavity or hole known as a «lacune». Traces of tiny haemorrhages may also be visible in one-third of patients. The latest cerebral imaging studies show that it is mainly the accumulation of minor infarcts in the brain that explains the severity of the disease during CADASIL.

The lesions in the white matter and the deep infarcts are due to a reduction in cerebral perfusion. A decrease in blood flow in the brain was observed within the white matter and sometimes, in a more diffuse manner, within patients’ brains. Permanent reduction in blood supply (and, therefore, in oxygen provided by the red blood cells) would appear to become more severe as the disease progresses and this explains the gradual accumulation of cerebral lesions and the increasing acuteness of symptoms.

CADASIL is a disease affecting mainly the walls of the small arteries (arterioles) in the brain and other organs. In many cases, the artery walls thicken; in some, they become fibrous. The smooth muscle cells in the central layer of the vessel wall (media) are abnormal or are gradually disappearing. Around them, there is a granular substance called GOM (granular osmiophilic material) which is typical of the disease and visible under an electron microscope. The exact origin of the GOM deposits is currently unknown. Recent work has shown that part of the Notch3 gene, which is a receptor on the surface of the membranes of smooth muscle cells, builds up near the GOM in the vessel walls. Recent research in human subjects and mice with the genetic abnormality showed that the wall of the small arteries did not contract or dilate normally. It may be that the narrowing of certain vessels, in addition to this abnormal reaction, produces the loss of perfusion observed in CADASIL patients.

We do not yet know why mutations in the Notch3 gene, which lead to an abnormality in the Notch3 receptor of the smooth muscle cell in the blood vessel, also lead to a build-up of protein, the appearance of GOM and the degeneration of smooth muscle cells in the vessel wall. The important part played by the Notch3 gene in the development of small arteries has, however, been clearly demonstrated.

No specific preventive treatment for this disease is known to date in CADASIL patients. Because of the occurrence of cerebral infarcts, aspirin is traditionally used as secondary prevention but the benefit of this treatment when the disease is already present has not been demonstrated. The possible occurrence of intracranial haemorrhages, although rare, suggests that the use of anticoagulants would, on the other hand, be risky.

For migraine with aura, vasoconstrictors are not recommended because of the theoretical risk of a reduction in cerebral blood flow in patients in a precarious haemodynamic condition with decreased cerebral blood flow. NSAIDs and analgesics are therefore recommended as first-line treatment of migraine.

The usefulness of acetylcholinesterase inhibitors was recently assessed as a means of helping patients with cognitive difficulties. This study found no significant treatment effect of donepezil on cognition as assessed by the primary efficacy measure but improvements were noted on several measures of executive function.

All the hypotensive treatments (neuroleptics, anti-hypertensive agents) must be used with care because of the possible risk of a decrease in cerebral blood flow in patients with reduced cerebral perfusion.

On the other hand, physiotherapy is essential and must be widely prescribed when motor signs and difficulties with walking and balance are present, especially after a stroke. Speech therapy is prescribed to improve communication and language abilities when necessary.

Psychological support is crucial at every stage of the disease, both for the patient and for the family and carers. It should include ways of dealing with the psychological consequences resulting from neurological deficiency, an assessment of psychological disorders directly linked to the disease, ways of dealing with the consequences of the handicap within the family unit and psychological counselling because of the familial and hereditary nature of the disease.

Current research work covers two areas:

1) clinically, there is a need to define all the clinical and MRI parameters required to set up therapeutic testing in the future for a rare disease that develops slowly, over several decades, and to gain greater insight into prognostic factors and factors that might explain the variable degrees of severity of this disease, 2) there is a need for research into the molecular mechanisms that lead from the genetic abnormality in the Notch3 gene to the lesions observed in the walls of the blood vessels. This is being done using animal models of the disease.

For further information regarding this disease and networks of expert center, please click here.

Pharmacien de formation et diplômée de l’ESSEC, Marion Pineau possède plus de 20 ans d’expérience en gestion de projet marketing et communication dans les domaines de la santé, prévention et bien-être. Son expertise couvre aussi bien la communication scientifique et institutionnelle que la coordination de projets impliquant médecins, patients et associations.

Au sein du CERVCO, elle pilote le développement des actions du centre, notamment l’organisation des Réunions de Concertation Pluridisciplinaires, les projets PNDS et le suivi des parcours de soins pour les maladies rares vasculaires du cerveau et de l’œil. Elle assure également le lien avec la plateforme d’expertise Paris Nord, la filière BRAIN-TEAM et le réseau européen VASCERN pour renforcer les synergies et favoriser l’innovation au bénéfice des patients.

Passionnée par la transmission et l’accessibilité de l’information en santé, elle contribue activement à la visibilité du CERVCO, notamment via son site internet, en veillant à rendre les contenus clairs et accessibles à tous les publics concernés (patients, professionnels de santé, associations).

D’abord secrétaire dans le secteur privé dés 1986, Solange Hello a intégré l’équipe du Service de Neurologie de l’hôpital Lariboisière en 2001. Elle a initialement exercé les fonctions de secrétaire de recherche et s’est investie dans le suivi de Projets Hospitaliers de Recherche Clinique concernant les maladies vasculaires cérébrales rares. Elle assure la fonction de secrétaire pour le CERVCO depuis le 1er janvier 2007.

Après l’obtention d’un doctorat en chimie de l’Université Claude Bernard Lyon I en 2005 et quelques années de recherche fondamentale Abbas Taleb a suivi une formation d’Attaché de Recherche Clinique (ARC) à l’institut Leonard De Vinci à Paris en 2010. Au décours de cette formation, il a intégré l’équipe du CERVCO et exerce actuellement la fonction de coordinateur d’essais cliniques. Il est responsable du recueil de données concernant les cohortes maladies rares.

Fanny Fernandes est docteur en Neurosciences. Après 15 ans de recherche préclinique en neurobiologie, sur les processus de myélinisation et de développement des glioblastomes, elle s’est tournée vers la recherche clinique en suivant les enseignements du DIU FIEC. Elle a ensuite animé le réseau national de recherche clinique FCRIN CRI-IMIDIATE sur les maladies auto-inflammatoires et auto-immunes puis le FHU ADAPT autour du développement de la médecine personnalisée en psychiatrie. Au sein du CERVCO elle anime le programme de recherche RHU Trt_cSVD qui a pour objectif de lutter contre les maladies des petits vaisseaux cérébraux en utilisant des approches pluridisciplinaires pour aboutir à des propositions innovantes pour la prise en charge des patients.

Diplômée d’un doctorat en pharmaco-oncologie, Estelle Dubus s’est d’abord intéressée à l’inhibition de l’angiogenèse dans les tumeurs pédiatriques comme cible thérapeutique et à la caractérisation des mécanismes de résistance associés. Au travers du programme de médecine personnalisée MAPPYACTS (#NCT02613962 ), elle a mis en place et coordonné un réseau national et européen de développement de modèles précliniques de tumeur pédiatrique en rechute. Après 15 ans en oncologie, elle a repris l’animation du DHU NeuroVasc et a structuré la recherche clinique au sein du département de neurologie. Aujourd’hui, chef de projet de la FHU NeuroVasc2030, elle anime le réseau neurovasculaire francilien dans le but de faire émerger de nouveaux projets : de la conception à la publication, coordination des équipes, animation des réseaux professionnels et veille au bon déroulement scientifique, réglementaire et budgétaire de chaque étape. Au sein du CERVCO, elle coordonne les essais cliniques et la remontée des données de file active, aide à la structuration des cohortes et bases de données, accompagne les collaborations et la réponse aux appels à projet.

Marie-Hélène De Sanctis est psychologue spécialisée en neuropsychologie au sein du service de Neurologie de l’Hôpital Lariboisière depuis 2017. Elle réalise des évaluations neuropsychologiques, anime des ateliers d’Éducation Thérapeutique du Patient et assure le suivi et le soutien psychologique des patients et de leurs proches. Elle intervient également au CERVCO pour l’évaluation neuropsychologique des patients atteints de maladies vasculaires rares du cerveau et de l’œil. Chargée de cours invitée à l’Université Paris 8, elle est également co-autrice d’une publication sur les manifestations insulaires en neuro-oncologie.

Sonia Reyes est psychologue à l’Assistance Publique. Elle a débuté son activité dans le Service de Neurologie du Pr. Bousser à l’hôpital Lariboisière et parallèlement au Centre de Neuropsychologie et du Langage dirigé par le Pr. Bruno Dubois à la Salpêtrière. Elle y a acquis une compétence particulière dans le dépistage de troubles cognitifs associés aux pathologies neurodégénératives et vasculaires du cerveau. Elle est actuellement psychologue au sein du département de neurologie de l’hôpital Lariboisière où elle prend en charge l’évaluation neuropsychologique des patients. Elle assure également la prise en charge psychologique de ces patients et de leur famille.

Au sein du CERVCO, elle assure l’évaluation neuropsychologique des patients, leur suivi, le soutien psychologique des patients et des familles. Enfin, elle participe des travaux de recherche clinique sur les troubles cognitifs au cours des pathologies neuro-vasculaires rares.

Aude Jabouley est psychologue à l’Assistance Publique depuis 9 ans. Elle a commencé à travailler en consultation mémoire dans les Hôpitaux Vaugirard-Gabriel Pallez et Paul Brousse. Elle y a acquis une compétence particulière dans le dépistage de troubles cognitifs associés aux pathologies neurodégénératives et vasculaires du cerveau. Depuis 7 ans et demi, elle est psychologue au sein du pôle « neuro sensoriel tête et cou » du Groupe Hospitalier Lariboisière-Fernand Widal où elle prend en charge l’évaluation neuropsychologique des patients. Elle assure également la prise en charge psychologique de ces patients et de leur famille.

Au sein du CERVCO, elle assure l’évaluation neuropsychologique des patients et leur suivi ainsi que le soutien psychologique des patients et des familles. Enfin, elle effectue actuellement des travaux de recherche clinique sur les troubles cognitifs au cours des pathologies neuro-vasculaires rares, en particulier la maladie de CADASIL.

Carla Machado est psychologue à l’Assistance Publique depuis 2012. Elle a commencé son activité clinique dans le service de Consultation Mémoire à l’hôpital Albert Chenevier où elle a développé une compétence dans l’évaluation des troubles cognitifs associés aux maladies neurodégénératives. Depuis, elle a rejoint l’équipe de psychologue dans le service de Neurologie du groupe hospitalier Lariboisière-Fernand Widal où elle prend en charge l’évaluation neuropsychologique des patients. Elle assure également la prise en charge psychologique de ces patients et de leur famille.

Au sein du CERVCO, elle assure les entretiens cliniques au sein des consultations multidisciplinaires pré symptomatique dans la maladie de CADASIL et participe aux consultations neurologiques dans le cadre de la remise des résultats génétiques. Elle participe également à des protocoles de recherche clinique sur les maladies neuro-vasculaires rares et est responsable du programme d’éducation thérapeutique du patient (ETP) pour l’angiopathie de moyamoya.

Le Professeur Homa Adle-Biassette est Chef du Service d’Anatomie et de Cytologie pathologique. Elle est Professeur d’Anatomie Pathologique. Elle est également membre de l’équipe INSERM 1141. Son intérêt principal est la neuropathologie et plus particulièrement le développement du système nerveux central. Elle a publié plus de 100 articles scientifiques dans le domaine de la neuropathologie.

Le Docteur Valérie Krivosic est ophtalmologiste, spécialisée dans les pathologies médicales et chirurgicales de la rétine. Après avoir réalisé un DEA dans l’unité INSERM dirigée par le professeur Tournier-Lasserve à l’université Paris VII, elle a été chef de clinique dans le service d’ophtalmologie dirigé par le professeur Gaudric à l’hôpital Lariboisière à Paris pendant 3 ans. Elle a ainsi acquis une compétence dans les pathologies de la vascularisation rétinienne tant sur le plan chirurgical (pour la rétinopathie diabétique par exemple) que sur le plan médical. Elle exerce actuellement son activité professionnelle à plein-temps à l’hôpital Lariboisière où elle se consacre à une activité chirurgicale et de recherche clinique sur les nouveaux médicaments de la rétine. Dans le cadre du CERVCO, elle prend en charge plusieurs affections des petits vaisseaux rétiniens telles que la vitréorétinopathie exsudative familiale, les télangiectasies maculaires idiopathiques ou la maladie de Von Hippel Lindau.

Ancien interne des hôpitaux de Paris, François NATAF a ensuite exercé la fonction de Chef de Clinique-Assistant des Hôpitaux puis de praticien hospitalier dans le service de neurochirurgie à l’hôpital Sainte-Anne à Paris de 1997 à 2022. Depuis 2022 il est praticien hospitalier dans le service de Neurochirurgie à l’hôpital Lariboisière à Paris.

Durant cette période, il a contribué au démarrage sur Paris et en France de l’activité de radiochirurgie, initialement et principalement sur les malformations artério-veineuses cérébrales. Il poursuit cette activité associée également à une activité chirurgicale au bloc opératoire.

Un équipement de radiochirurgie de dernière génération (ZAP-X) est en cours d’installation sur le site de l’hôpital Lariboisière. L’activité de radiochirurgie est une UF du service de Neurochirurgie de Lariboisière, sous la direction du Pr Hennequin, radiothérapeute à Saint-Louis. Cet équipement est l’aboutissement d’un projet du GHU Nord associant 7 services dans 3 hôpitaux (Lariboisière, Saint-Louis, Beaujon) en collaboration avec l’Institut de Radiothérapie Hartmann (dans le cadre d’un GCS). L’organisation médicale du GCS intègrera un conseil scientifique.

François NATAF est l’actuel Directeur médical du GCS de radiochirurgie. Les travaux en cours portent notamment sur la radiochirurgie des malformations vasculaires cérébrales (MAV et cavernomes).

Ancien interne des hôpitaux de Paris, le Docteur Anne-Laure Bernat est praticien hospitalier dans le service de Neurochirurgie de l’hôpital Lariboisière. Elle a réalisé un fellowship Clinique à Toronto au Canada. Au sein du département de neurochirurgie, elle prend en charge plus spécifiquement les maladies vasculaires neurochirurgicales, les méningiomes et les adénomes hypophysaires. Son activité de recherche scientifique en collaboration avec les équipes médicales intéressées porte essentiellement sur les maladies vasculaires neurochirurgicales et la gestion des patients victimes d’hémorragie méningée anévrismale. Dans le cadre du CERVCO, elle prend en charge les patients atteints d’anévrismes intra-crâniens, de malformations artério-veineuses et d’angiopathie de MOYA MOYA.

Le Professeur Sébastien Froelich est chef du service de Neurochirurgie de l’Hôpital Lariboisière. Ses travaux de recherche concernent plus particulièrement les affections de la base du crâne et certaines tumeurs comme le chordome. Dans le cadre du CERVCO, il prend plus particulièrement en charge les patients atteints de cavernomes cérébraux et d’angiopathie de moyamoya.

Ancien interne des hôpitaux de Paris et chef de clinique-assistant, Caroline Roos est neurologue, praticien hospitalier temps plein et responsable du Centre d’Urgences des Céphalées de l’hôpital Lariboisière. Elle s’est spécialisée dans la prise en charge des patients souffrant de céphalées primaires et secondaires Elle a participé à de nombreux travaux de recherche et fait partie du comité pédagogique du diplôme Inter-Universitaire Migraine et Céphalées. Dans le cadre du CERVCO, elle prend en charge les patients atteints d’ataxie épisodique et de migraine hémiplégique familiale ou sporadique. Elle est aussi référente pour la prise en charge des patients suivis dans le cadre du CERVCO, souffrant de céphalée.

Le Dr Vittorio Civelli est neuroradiologue interventionnel. Après une formation médicale et spécialisée à Milan (Italie) et un clinicat à l’hôpital Foch (Surennes) et à l’hôpital Lariboisière, il occupe depuis 2016 un poste permanent de Praticien Hospitalier dans le service de neuroradiologie interventionnelle dirigé par le Pr HOUDART où il se consacre à la prise en charge des pathologies vasculaires cérébrales et médullaires (anévrismes, fistules artério-veineuses, AVC, MAV), à la sclérose percutanée des angiomes et des anomalies vasculaires superficielles avec un intérêt clinique et de recherche principalement consacré au traitement de la pathologie sténosante veino-durale (traitement endovasculaire de l’acouphène pulsatiles et de l’hypertension intra-crânienne dite idiopathique), de l’hypotension du LCR, de la maladie de Moya-Moya et des malformations vasculaires superficielles.

Depuis 2014, le Dr Marc-Antoine Labeyrie est praticien hospitalier temps plein au sein du DMU neurosciences à l’hôpital Lariboisière. Il exerce la neuroradiologie interventionnelle et est spécialisé dans la prise en charge des pathologies artérielles et veineuses macrovasculaires de la tête, du cou et du rachis.

Au sein du CERVCO, il participe plus particulièrement aux RCP sur la maladie de Moyamoya et travaille sur le développement de nouvelles variables de phénotypage angiographique de cette maladie.

Ses autres thématiques de recherche sont : 1/ l’évaluation des techniques endovasculaires intracrâniennes innovantes (angioplastie de vasospasme, thrombectomie à la phase aigüe des AVC ischémiques, stenting des sinus latéraux dans l’hypertension intracrânienne idiopathique) ; 2/ L’épidémiologie des causes macrovasculaires rares d’ischémie cérébrale (carotid web, dissections artérielles cervicales et intracrâniennes) ; 3/ L’imagerie cérébrale quantitative (segmentation automatique de l’imagerie cérébrale à la phase aigüe des hémorragies sous arachnoïdiennes).

Professeur des Universités – Praticien Hospitalier, responsable de l’unité de Neuroradiologie Interventionnelle du Service de Neuroradiologie depuis 1997. Cette unité effectue annuellement 800 artériographies cérébrales et 500 interventions endovasculaires de la sphère cérébrale, ORL et médullaire par année. Il s’agit d’un des centres français ayant l’activité la plus importante dans ce domaine. L’activité clinique est supportée par une activité de recherche centrée sur l’évaluation des nouvelles techniques de traitement des anévrysmes intracrâniens, des malformations artério-veineuses cérébrales et de l’athérome des artères cérébrales.

Ancien Interne des hôpitaux de Paris, il a été Assistant Hospitalier Universitaire dans le service de Neurologie de l’hôpital Bichat et Chef de Clinique-Assistant dans le service de Neuroradiologie de l’hôpital Lariboisière. Il est Professeur de Neurologie à l’Université Denis Diderot depuis 2013, membre de l’Unité INSERM 1148 (Laboratory of Vascular Translational Science) et chef du département de Neurologie de l’hôpital Lariboisière. Il partage ses activités de soins entre la neurologie et la neuroradiologie interventionnelle pour la prise en charge des accidents vasculaires cérébraux et notamment des malformations vasculaires cérébrales. Ses travaux de recherche sont centrés sur le développement et l’évaluation de nouveaux traitements à la phase aigüe de l’accident vasculaire cérébral. Pr Mazighi est aussi dans la gouvernance de la FHU Neurovasc 2030, leader du work package 0.

Après un DES de Neurologie à Paris, Isabelle Crassard a effectué un clinicat à l’hôpital Lariboisière (Services de Neurologie et d’Angiohématologie). Elle est actuellement praticien hospitalier dans le département de neurologie de l’hôpital Lariboisière. Elle s’intéresse en particulier aux troubles de la coagulation à l’origine de certains accidents vasculaires cérébraux et aux maladies veineuses cérébrales. Dans le cadre du Centre Maladies Rares, elle prend plus particulièrement en charge les patients ayant une thrombose veineuse cérébrale.

Eric Jouvent est ancien interne et ancien Chef de Clinique – Assistant des hôpitaux de Paris. Il est Professeur des Universités en neurologie à l’Université Paris Diderot et Praticien Hospitalier dans le service de neurologie de l’hôpital Lariboisière. Il s’intéresse à la pathologie vasculaire cérébrale, notamment aux aspects cognitifs et comportementaux des maladies des petites artères cérébrales dont CADASIL.

Ses travaux de recherche portent sur les liens entre l’imagerie et les aspects cliniques dans les maladies des petites artères cérébrales et dans CADASIL, et en particulier sur le rôle du cortex cérébral.

Membre du comité exécutif de la FHU Neurovas2030, Pr Jouvent a un intérêt pour l’innovation et les nouvelles technologies en particulier autour de l’imagerie cérébrale.

Le Docteur Stéphanie Guey, Neurologue, ancien interne des Hôpitaux de Paris et titulaire d’une thèse de sciences en Génétique, est depuis septembre 2022 Maître de Conférences des Universités – Praticien Hospitalier (MCU-PH) au sein du centre de neurologie translationnel (CNVT) Lariboisière et de l’Université Paris Cité.

Au sein du CERVCO, (centre de référence dédié aux maladies vasculaires rares du cerveau et de l’œil), elle consacre son activité clinique et de recherche aux affections cérébrovasculaires rares de l’adulte et plus particulièrement les cavernomatoses cérébrales et les maladies vasculaires cérébrales d’origine génétique, en particulier celles liées aux anomalies des gènes COL4A1 et COL4A2.

Dr Guey a développé une expertise reconnue dans le diagnostic, la compréhension et le suivi de ces pathologies encore peu connues. Elle s’attache à améliorer le parcours de soins des patients et à favoriser le dialogue entre la recherche, les équipes médicales et les familles.

Membre du Conseil scientifique de l’Association COL4A1-A2, Dr Guey est engagée dans une collaboration étroite avec les représentants des patients pour favoriser la diffusion des connaissances, accompagner les familles et faire progresser la recherche dans une approche humaine et collective.

Le Professeur Dominique HERVE a initialement exercé la fonction de Chef de Clinique – Assistant des Hôpitaux au sein du service de neurologie vasculaire de l’hôpital Lariboisière dédiée à la prise en charge en phase aigüe des pathologies vasculaires cérébrales. Depuis Novembre 2006, Dominique HERVE est Praticien Hospitalier temps plein à Lariboisière et son activité clinique est centrée sur la prise en charge des maladies cérébrovasculaires rares. Il est Professeur Associé de Neurologie à l’Université Paris Cité depuis septembre 2025.

Au sein du Centre Neuro-Vasculaire Translationnel (CNVT) de l’hôpital Lariboisière, il est le responsable médical du Centre de Référence des maladies Vasculaires rares du Cerveau et de l’Oeil (CERVCO). Sa mission est pleinement dédiée au développement de ce centre de référence. Dans le cadre du CERVCO, son activité clinique et de recherche concerne principalement l’angiopathie de Moyamoya et les maladies génétiques des petites artères cérébrales (CADASIL et autres leucoencéphalopathies vasculaires génétiques). Il a récemment coordonné la rédaction de recommandations européennes concernant la prise en charge de l’angiopathie de Moyamoya sous l’égide de l’European Stroke Organisation (ESO). Il prend également en charge les patients atteints de cavernomatoses cérébrales et de forme familiale d’anévrysmes cérébraux.

Depuis 2022, il coordonne un groupe de travail européen dédié aux maladies cérébrovasculaires rares (NEUROVASC) au sein du réseau européen de référence pour les maladies vasculaires rares (VASCERN).

Le Professeur Hugues Chabriat est coordonnateur du centre de référence pour les maladies vasculaires rares du cerveau et de l’oeil (CERVCO). Ancien interne des hopitaux d’Ile de France (Cochin Port-Royal) et chef de clinique à la faculté de médecine de Saint-Antoine à Paris, il est professeur de neurologie à l’Université Denis Diderot (Paris VII), chef de service du Centre Neuro-vasculaire Translationnel (CNVT) à l’Hôpital Lariboisiere et co-responsable d’une équipe de recherche au sein de l’unité INSERM U1141.

Ses travaux de recherche concernent plus particulièrement les affections vasculaires rares des petits vaisseaux du cerveau, l’imagerie cérébrale des maladies artériolaires cérébrales et les troubles cognitifs d’origine vasculaire. Il participe avec l’équipe de génétique à l’étude de nouvelles familles de leucoencéphalopathies vasculaire dont l’origine reste à déterminer. Il développe avec d’autres chercheurs les outils d’imagerie pour évaluer, en particulier, l’évolution et les futures thérapeutiques de ces affections.

Il a publié plus d’une centaine d’articles ou de chapitres de livre consacrées aux leucoencéphalopathies vasculaires, à l’imagerie cérébrale des maladies des petits vaisseaux du cerveau et à CADASIL.