Rare Diseases

For each of the rare vascular diseases of the brain or eye linked to the CERVCO reference center, you will find below information documents concerning the characteristics of the disease and its management.

For each of the rare vascular diseases of the brain or eye linked to the CERVCO reference center, you will find below information documents concerning the characteristics of the disease and its management.

« Moyamoya » angiopathy is the term used to define the presence of an abnormal vascular network which develops because of gradual stenosis (narrowing) of the arteries at the base of the brain (upper end of the internal carotid artery or beginning of its branches anterior cerebral artery or middle cerebral artery). The abnormal vascular network appears gradually, to compensate for the reduction in blood flow downstream from the stenosis in the arteries at the base of the brain. It often has a « cloudy » or « hazy puff of smoke » appearance, which, in Japanese, is translated by « moyamoya ».

The abnormal vascular network can develop when the arteries at the base of the skull narrow as a result of an already known general or localized disease. These patients are described as having the « Moyamoya syndrome ». The term Moyamoya disease » is used when no specific disorder is associated with the arterial abnormalities.

This document was created by ORPHANET in collaboration with the Tanguy Moya-Moya association and CERVCO (D. Hervé, H. Chabriat).

Source: CADASIL, Orphanet Public Encyclopedia, April 2008

http://www.orpha.net/data/patho/Pub/fr/MoyaMoya-FRfrPub2373.pdf

What is Moyamoya disease?

Moyamoya disease is a rare condition affecting the blood vessels that supply the brain. It is characterized by the gradual narrowing, or even blockage, of the arteries located at the base of the skull, leading to an insufficient supply of blood, and therefore oxygen, to the brain. The resulting symptoms are usually paralysis of an arm or leg, headaches, vision and speech disturbances, or epileptic seizures. These symptoms may be permanent or temporary. Moyamoya disease usually occurs without any apparent cause. When it appears in association with another condition that causes a gradual narrowing of the arteries at the base of the brain, it is referred to as « Moyamoya syndrome » or secondary Moyamoya.

How many people does this disease affect?

The prevalence of Moyamoya disease (the number of people affected in a given population at a certain time) varies by population. In France, it is estimated to affect approximately 1 in 300,000 people. In Japan, where the disease was initially described, it is believed to be 10 times more frequent, with approximately 1 case in 30,000 people.

Who can be affected? Is it present everywhere in France and the world?

The disease affects all populations, but it is much more common in Japan and among people of Asian origin. Moyamoya disease primarily affects children between the ages of 5 and 15, but it can also occur in adults, particularly between the ages of 30 and 40. Girls seem to be affected more often than boys.

What causes this disease?

The exact cause of Moyamoya disease is unknown. It can occur in isolation (with no associated illness), and in such cases, it is referred to as Moyamoya disease. In a small number of cases, it runs in families, meaning that several family members have the disease. This suggests that genetic factors are involved, though no specific gene has been identified yet. Familial cases are very rare (see « Genetic Aspects »).

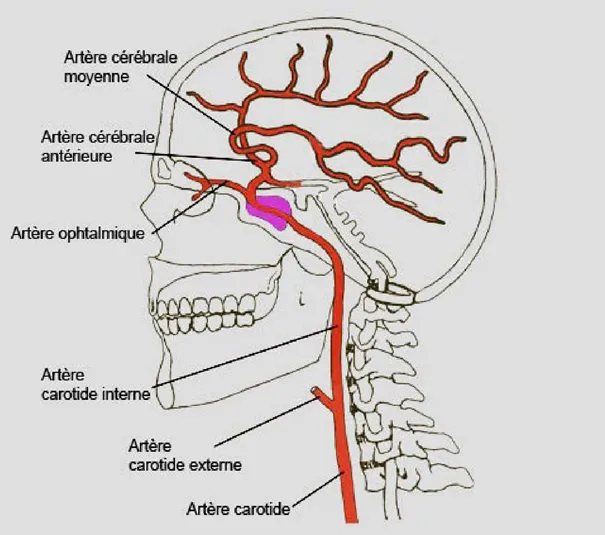

During the disease, the large arteries that supply blood to the brain (figure 1) gradually narrow (stenosis), which prevents blood from flowing normally. To compensate for this slowdown in blood circulation, other, finer vessels gradually develop. It is somewhat like a highway being congested and secondary roads being built to bypass the traffic jam. When observed through arteriography (see further details below), the network of newly formed small collateral vessels has a cloudy or « puff of smoke » appearance, which is referred to as « moyamoya » in Japanese.

Figure 1: The internal carotid artery is the main artery that supplies blood to the brain. It is generally affected in Moyamoya disease. It divides into the anterior cerebral artery and the middle cerebral artery, which can also become narrowed. (http://radiologynotes.servehttp.com/vascular/vascular.htm)

Sometimes, it is a consequence of another condition, such as sickle cell disease, Down syndrome, or a tumor at the base of the skull that has been treated with radiotherapy. In such cases, it is referred to as Moyamoya syndrome.

Is it contagious?

No, Moyamoya disease is not a contagious illness.

What are the symptoms?

The symptoms of the disease vary greatly from person to person.

In both children and adults, the disease mainly manifests through strokes (often referred to as « attacks » in common language). These occur when a part of the brain is suddenly deprived of blood supply (called ischemic stroke or cerebral infarction) or when a small blood vessel bursts and blood leaks into the brain (called hemorrhagic stroke or cerebral hemorrhage).

Strokes can cause various symptoms that appear suddenly. Often, this includes weakness or paralysis of a limb or one side of the body (hemiplegia), or a loss of sensation in part of the body (numbness, abnormal tingling). In practice, this may result in the person being unable to hold a fork, one or both legs giving way, or a sudden inability to move one arm, for example. In children, these issues sometimes occur when they are upset or crying.

Strokes can also cause speech or language problems (difficulty speaking or regression of speech), vision problems, and issues with balance and coordination (making walking clumsy).

These problems may be permanent or temporary (referred to as transient ischemic attacks).

Children may also suffer from severe headaches, dizziness, and experience academic delays due to learning or memory difficulties.

Finally, some patients may also have epileptic seizures. The symptoms of these seizures vary: movements or convulsions (muscle jerks, tremors, stiffness), sensory disturbances (tingling, numbness, auditory or visual hallucinations), psychological issues (panic, memory problems, confusion, loss of consciousness, blackouts), or even excessive salivation, urinary incontinence, etc. The seizures can affect the entire body (generalized seizures), usually accompanied by loss of consciousness, or just one part of the body (a limb, for example) or one side of the body (partial seizures).

In some cases, repeated strokes can eventually damage intellectual functions, and some children may become « slower » or begin to experience learning difficulties. Others may lose some of the skills they had previously acquired (such as language). Similarly, in adults, intellectual abilities may decline due to the disease.

Adults with Moyamoya disease experience the same symptoms as children, but strokes are most often caused by cerebral hemorrhage. However, as in children, they may also be caused by cerebral infarction.

What explains the symptoms?

Most symptoms are caused by insufficient blood flow to the brain. Certain areas of the brain do not receive enough oxygen to function properly. The symptoms depend on the affected area: vision problems, motor issues, sensory disturbances, etc. Repeated episodes of oxygen deprivation can permanently damage the affected areas, explaining why some effects are lasting.

Additionally, particularly in adults, while the newly formed small supplementary blood vessels provide a minimum blood supply, they are more fragile than normal vessels. There is, therefore, an additional risk of bleeding in these vessels, which can lead to cerebral hemorrhages. Moreover, these abnormal small vessels can also become blocked.

What is the progression of the disease?

The narrowing of the arteries supplying blood to the brain is progressive: without treatment, the symptoms worsen, and the risk of stroke increases.

The main risk of the disease is the development of permanent neurological problems, particularly the possible occurrence of intellectual impairment due to brain damage. Loss of speech or movement disorders are also common, but rehabilitation can sometimes help reduce the severity of the aftereffects. About half of the patients may experience intellectual deterioration.

In some cases, Moyamoya disease can be fatal (about 10% of adults and 4% of children), usually due to a cerebral hemorrhage.

How is Moyamoya angiopathy diagnosed?

When the first symptoms appear, brain imaging through magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is often performed first. This painless examination involves obtaining detailed images of the brain by placing the patient in a machine that produces a magnetic field. It allows doctors to detect brain lesions (hemorrhage or infarction).

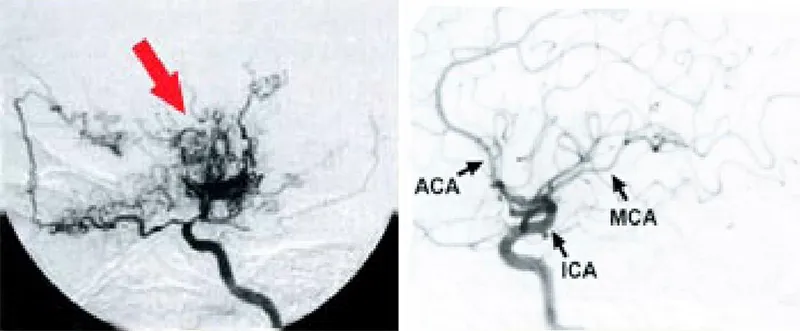

However, the examination that confirms the diagnosis of Moyamoya disease is cerebral angiography. This is a radiological examination using X-rays, which allows observation of the blood vessels after injecting a « contrast agent » into the blood to make the vessels more visible. In individuals with Moyamoya disease, the images of the brain’s blood vessels are very telling: they reveal the presence of an abnormal network of « smoke-like » vessels (see figure 2).

Figure 2: On the left, an angiogram of a person with Moya Moya disease. Small « smoke-like » vessels appear to compensate for the narrowing of the internal carotid artery or its branches (anterior or middle cerebral arteries). On the right, an angiogram shows normal arteries.

MCA: Middle cerebral artery

ACA: Anterior cerebral artery

ICA: Internal carotid artery

This examination also helps to assess the severity of arterial narrowing.

What do additional tests consist of? What are they for?

The discovery of Moya Moya disease requires investigating any possible cause to determine if there is an underlying condition that could explain it, or if it is an idiopathic form (i.e., without an apparent cause).

A brain MRI can already rule out certain causes, such as congenital brain vessel malformations or the presence of a tumor. However, other tests are generally conducted. Blood tests can help detect blood disorders (such as protein C deficiency, which promotes the formation of blood clots – small plugs formed by blood platelets – or sickle cell disease, a condition characterized by abnormal red blood cells that can block blood vessels). Together with urine tests, these tests can also help detect metabolic diseases (such as homocystinuria, which can sometimes cause strokes).

Moya Moya syndrome can be associated with other diseases, such as neurofibromatosis type 1 (or Recklinghausen disease), a genetic disorder characterized by café-au-lait spots, « freckles » in the armpits and groin, small skin growths, or lumps under the skin (neurofibromas). If the diagnosis of neurofibromatosis has not already been made, it is based on ophthalmological and dermatological examinations.

Can this disease be confused with other conditions? Which ones? How can you tell the difference?

Strokes are relatively common in the general population, especially among older people, smokers, or those with high blood pressure, diabetes, or high cholesterol. In adults, Moya Moya disease may not necessarily be considered at the onset of stroke symptoms. However, cerebral angiography can direct the physician towards a diagnosis of Moya Moya disease.

In children, on the other hand, strokes are extremely rare. They can be caused by several diseases, which will be systematically investigated, as explained above.

What are the risks of transmission to children? What are the risks for other family members?

In the vast majority of cases, Moya Moya disease is sporadic, meaning there is only one case within a family.

Very rarely, the disease is familial (with at least two cases occurring in the same family). Familial forms are, however, exceptional in Europe (around 2%). In Japan, where the disease is more common, about 10% of Moya Moya cases are familial. In these families, the mode of transmission from one generation to another is not clearly determined. Researchers believe that the risk of relatives developing the disease is slightly increased, but it cannot be precisely evaluated.

However, when Moya Moya syndrome is a consequence of an inherited genetic disease (such as neurofibromatosis), there is a risk that siblings may also have this genetic disease (though it is impossible to predict if they will also develop Moya Moya syndrome).

Can this disease be detected in at-risk individuals before it manifests?

In exceptional cases, a brain MRI performed for a completely different reason (such as trauma) may reveal narrowing of the cerebral arteries before any symptoms appear.

Can prenatal diagnosis be made?

No, prenatal diagnosis is not possible.

Is there a treatment for this condition? What benefits can be expected from the treatment?

There is no treatment to prevent the narrowing of the brain arteries, but there are ways to limit the symptoms.

Surgery

Most often, a surgical operation can be considered, especially in early forms of the disease. The choice of such an intervention can be difficult and is made after consultation between the family and the medical teams, based on the patient’s age, condition, and symptoms. However, not all patients are good « candidates » for surgery, which can sometimes be more dangerous than beneficial.

The goal of the operation is to provide blood to areas of the brain suffering from a lack of oxygen. This is done by « redirecting » vessels that supply other regions (such as the scalp, temporal muscles, etc.) and bringing them to the brain. These redirected vessels will then develop and provide « palliative » irrigation, bypassing the narrowed cerebral arteries (this is referred to as revascularization). Several surgical techniques are used to redirect the vessels:

The difference in efficacy between these surgical techniques is not well established, and surgeons generally choose the least aggressive and most easily feasible solution, especially for young children. In case of failure, another surgical approach may be considered. Each operation is discussed on a case-by-case basis.

Medications

Since some cerebral vessels are narrower due to the disease, there is a higher risk of blood clots forming and contributing to the obstruction of these vessels. Medications that prevent platelet aggregation and thus the formation of clots (antiplatelet agents), such as aspirin, are sometimes given to patients as a preventive measure, but their efficacy is not clearly proven. Moreover, these medications can increase the risk of bleeding in the brain.

In certain cases, vasodilator medications (calcium channel blockers) may be prescribed. They cause the blood vessels to dilate (widen), allowing blood to flow more easily. They can sometimes help alleviate headaches.

In the event of seizures, antiepileptic medications may be prescribed.

Rehabilitation

After a stroke, rehabilitation should be organized by a multidisciplinary team to try to recover as many faculties as possible, including language, movement, and cognitive abilities. Both children and adults often have impressive recovery capabilities that must be fully exploited through appropriate exercises.

Thus, physiotherapy is essential for managing any motor disorders (walking, balance, coordination of movements, etc.). In cases of speech disorders, speech therapy is recommended. Physiotherapy and speech therapy sessions are reimbursed by Social Security.

In cases of significant sequelae, psychomotor therapy sessions can help the patient cope with their disability and accept their body image, allowing them to adapt to their environment.

Regarding the management of intellectual disorders, it can involve participation in group sessions (with other patients, for example), stimulating the patient, preventing isolation, and limiting the feeling of being a burden to those around them.

In cases of loss of autonomy (intellectual slowdown, behavioral disorders, significant motor difficulties), the patient may need specialized home assistance or even hospitalization in a specialized medical facility to assist with daily living (hygiene, nutrition).

What are the benefits and risks of treatment?

Generally, children respond better to surgery than adults.

The prognosis for operated individuals is quite good, although some improvements may only be visible 6 to 12 months after the procedure. Multiple interventions may sometimes be necessary.

However, these are heavy operations, and the risks associated with anesthesia are higher in patients due to poor brain vascularization and vessel fragility (high risk of hemorrhage). It is important to discuss this with the anesthetist before the operation to assess the risks involved.

Additionally, when a patient has suffered a severe and prolonged stroke, the damaged areas of the brain are unfortunately permanently affected. Even if the patient can « recover » certain abilities, they may present permanent sequelae on which surgical intervention will have no effect.

Is psychological support advisable?

At various times, both the family and the patient may feel the need for psychological support.

The announcement of the diagnosis is a difficult moment, as it concerns a disease that affects the brain and can potentially be disabling both physically and mentally. Moreover, the evolution of the disease is unpredictable, and the fear of a significant stroke (which can cause serious irreversible damage, such as paralysis, vision problems, etc.) contributes to plunging some patients or their parents into anxiety that is difficult to bear. For this reason, the support of a psychologist can be greatly helpful.

When the disease occurs in a child, it is particularly difficult for parents to learn how to care for the child without overprotecting them, to maintain communication within the couple and family, and to manage feelings of jealousy or even guilt that the siblings of the sick child may experience. Additionally, the decision-making process regarding a possible operation can be difficult, and parents need guidance and support.

Various relaxation methods can also be useful for learning to manage anxiety and coping with the illness.

What can one do on their own to help with recovery?

There are no specific recommendations, but it is advisable to maintain a good lifestyle, and for adults, to avoid smoking (as it increases the risk of stroke).

Similarly, contraceptive pills or hormone treatments given during menopause can increase the risk of cardiovascular diseases (in addition to the risk related to Moya Moya disease). Generally, to avoid any unnecessary risk-taking, hormone treatment is only maintained if it provides real benefits for menopause-related symptoms (such as treatment for hot flashes), and this for a limited duration.

Additionally, a pill containing only progestogens (without estrogens) is generally preferred over the conventional pill

How to get follow-up care?

Follow-up for individuals with Moya Moya disease is conducted in specialized hospital neurology consultations. The frequency of visits and examinations is determined by the medical team.

However, certain symptoms should alert the patient or their parents and prompt them to seek emergency care.

For instance, a stroke may manifest as sudden vision or speech disturbances, sudden difficulties in moving a limb (for example, it may become difficult to write), or coordination issues. Likewise, in the case of severe headaches, it is advisable to consult a doctor promptly.

What information should be known and communicated in an emergency?

In an emergency, it is crucial to inform the doctors about the diagnosis of Moya Moya disease. Given the significant risks associated with anesthesia, it is necessary for the patient to be managed by an experienced anesthetist familiar with this disease and its specifics.

Finally, it is imperative to inform the healthcare staff about the ongoing treatments and their dosages. This precaution helps avoid incompatible drug combinations and potential overdoses.

Can this disease be prevented?

No, as of now, there is no way to prevent the occurrence of Moya Moya disease.

What are the consequences of the disease on family, professional, social, school, and sports life?

Being affected by a disease that impacts the brain, associated with the risk of physical and/or intellectual disability, is extremely challenging. However, it is impossible to predict whether patients will have permanent sequelae and which functions will be affected (vision, speech, walking, etc.). The consequences of the disease vary significantly from one person to another.

It is entirely possible to lead a normal life while having Moya Moya disease.

However, in some individuals, strokes may leave debilitating sequelae, compromising the patient’s autonomy.

Thus, in some cases for adults, ceasing professional activity may become necessary, or at least a reorientation or reorganization of work hours. Additionally, in the event of a stroke, hospitalization followed by often lengthy rehabilitation is essential to enable patients to recover and regain as many functions as possible.

For many children, normal schooling can be ensured and adapted through an Individualized Reception Project (PAI) or a Personal Schooling Project (PPS). This is an agreement involving the family, the school, and the school doctor, aimed at meeting the child’s needs and informing teachers about the disease.

For children with significant deficits (vision and speech disorders, significant learning difficulties), schooling in a class for disabled students (CLIS), with fewer students and adapted teaching, may be necessary and more reassuring. CLIS also allows for time for essential sessions of speech therapy, psychomotricity, or physiotherapy.

In certain cases, education and care can take place at home through the Special Education and Home Care Service (SESSAD).

Pregnancy

It is possible to have children while affected by Moya Moya disease, with appropriate medical follow-up. Given the risks associated with anesthesia, necessary precautions must be taken. It is therefore important to discuss any desire for pregnancy or an ongoing pregnancy with your doctor.

Where is research currently?

Research aims to better understand the mechanisms responsible for the narrowing of the cerebral arteries. The rare familial cases are studied to try to identify one or more genes responsible for the disease.

Clinically, therapeutic trials are being considered, particularly to evaluate the effectiveness of « vasodilator » or « neuroprotective » medications.

« Moyamoya » angiopathy is the term used to define the presence of an abnormal vascular network which develops because of gradual stenosis (narrowing) of the arteries at the base of the brain (upper end of the internal carotid artery or beginning of its branches anterior cerebral artery or middle cerebral artery).The abnormal vascular network appears gradually, to compensate for the reduction in blood flow downstream from the stenoses in the arteries at the base of the brain. It often has a « cloudy » or « hazy puff of smoke » appearance, which in Japanese, is translated by « moyamoya ».

The abnormal vascular network can develop when the arteries in the base of the skull narrow as a result of an already known general or localized disease. These patients are described as having the « Moyamoya syndrome ». The term « Moyamoya disease » is use when no disease is associated with the arterial abnormalities..

The frequency of the disease varies according to the population. In Japan, where the disease is most commonly found, the diagnosis of Moyamoya is suggested by a radiological examination of the brain without any symptoms in one in 2000 cases. The prevalence of Moyamoya is estimated at approximately 3 out of 100,000 cases and its incidence (number of new cases) is estimated at 0.35 cases in 100,000 people per year.

In Europe or the USA, Moyamoya disease is thought to be 10 times less frequent. The estimated frequency is approximately 0.3 cases per 100,000 people in France, approximately 180 cases. The number of new cases in the USA is 0.086 cases/100,000 people per year but it varies between 0.03 among non-Asians and 0.3 cases/100,000 people per year among Asians.

In both Asia and Europe, the disease appears to be more frequent in women (1.3 to 2.4 women for one affected man).

The frequency of the familial forms varies between 2% and 20% in Japan depending on the series. Familial forms are rare in Europe.

The onset of clinical signs occurs before the age of 10 in one-half of all cases (Children form of Moyamoya disease). It then occurs most frequently between the ages of 25 and 50 (adult form of the disease).

In adults, Moyamoya disease can cause the following:

Hereditary forms of Moyamoya disease have been observed mainly in Japan where familial cases represent 10% of cases. They are unusual in Europe.

Moyamoya syndrome in adults produces a combination of neurological disorders associated with the cerebral abnormal vascular network and signs of the associated general disease.

The commonest general pathology associated with Moyamoya syndrome is:

Other associations have been reported but some of them may have occurred randomly: arterial trauma, cranial trauma, congenital or acquired heart defects, aortic coarctation, arterial aneurysm, polycystic kidneys, Fanconi’s anaemia, diabetes, abnormal thyroid function etc.

Moyamoya disease begins with stenosis (or narrowing) of the large arteries at the base of the skull. The innermost layer of the artery wall (intima) thickens, where the muscle cells, which are usually located in the centre of the wall, have migrated and proliferated. This thickening is associated with changes in the fibrillary components of the vessel wall. Unlike the Moyamoya syndrome, which can be associated with inflammation in the vessel, wall, in Moyamoya disease there is no inflammatory damage to the wall. In Moyamoya disease, the exact mechanisms leading to the thickening of the vascular wall remain unknown. The very slow, gradual thickening of the arteries at the base of the skull are thought to cause: 1) dilation of the existing vessels downstream from the stenosis (the existing vessels dilate to the maximum to compensate for the drop in blood supply) and 2) development of new vessels through the production of angiogenic factors (factors stimulating the growth of new vessels e.g. bFGF or basic Fibroblast Growth Factor) in the poorly-supplied cerebral tissue.

It is the development of this new « abnormal » vascular network that produces the very specific appearance observed during arteriography which is typical of Moyamoya disease (development of numerous small vessels grouped together to form the “hazy puff of smoke” appearance.

Despite the development of this « neo-vascularisation », cerebral blood supply can remain inadequate, causing cerebral infarcts. « Neo-vascularisation », consisting mainly of small, very fragile vessels, can also lead to cerebral haemorrhage.

A diagnosis of Moyamoya disease or syndrome is always suggested by the results of a brain scan, an MRI of the brain or an examination of the vessels using an angioscanner or arteriography of the brain. The examination is most commonly carried out in patients with neurological deficiencies or headache.

According to the Japanese Ministry of Health, diagnosing Moyamoya disease with certainty is based on the presence of the following criteria on the arteriography, MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) with MRA (magnetic resonance angiography) or autopsy:

A « probable » diagnosis of Moyamoya disease is considered when the vascular abnormalities are not bilateral.

Unilateral forms of Moyamoya disease (« probable » disease) are more frequent in adults. In a Japanese study, 7% of forms that were unilateral at the time of diagnosis became bilateral during the 6-year monitoring period.

Treatment of Moyamoya disease is complex and must be discussed by multidisciplinary teams involving, in particular, neurologists, neurosurgeons and anaesthetists.

Depending on the patient’s age and general condition, the type of cerebral lesions (infarction or haemorrhage) and the stage reached by the disease, various therapeutic options are available:

These various treatments may be combined. They are discussed against the background of the stage of the illness, the patient’s age, the technical possibilities and the progress of the disease.

In Japan, 10% of Moyamoya cases appear to be familial in origin (at least two relatives have been diagnosed in the same family). In a small number of families, transmission is autosomal dominant (the genetic abnormality responsible for the disease affects as many men as women and adults have a one in two chance of passing it on to their children) but penetrance is weak. The number of cases within a family is therefore low (often two or three cases). In most families, there is probably some polygenic susceptibility. In Japan, when a case of Moyamoya disease has been diagnosed, the likelihood of identifying another case within the patient’s family is thought to be 34 times higher than the risk of the onset of the disease among the general population.

No gene responsible for Moyamoya disease has yet been identified. A number of chromosome locations have been reported, in chromosomes 3, 6, 8, 12 and 17 but none of these has been confirmed.

In Europe, familial forms seem to be extremely rare. A very small number of familial cases have been observed in Italy, Belgium and France (fewer than 5 families in all). The risk of finding another case within the same family remains unknown.

In adults, after diagnosis, the disease develops very slowly in most cases, over several decades. The prognosis depends mainly on the severity of the sequelae from cerebral vascular accidents occurring as part of the illness. When Moyamoya disease is confirmed (bilateral damage) and has already caused a cerebral infarct, the risk of a further cerebral vascular accident is thought to be approximately 10% per year in the absence of any surgical treatment. Certain studies suggest that the risk would be reduced two- or threefold, approximately, by surgical treatment aimed at improving the blood supply to the brain.

For further information regarding this disease and networks of expert center, please click here.

Pharmacien de formation et diplômée de l’ESSEC, Marion Pineau possède plus de 20 ans d’expérience en gestion de projet marketing et communication dans les domaines de la santé, prévention et bien-être. Son expertise couvre aussi bien la communication scientifique et institutionnelle que la coordination de projets impliquant médecins, patients et associations.

Au sein du CERVCO, elle pilote le développement des actions du centre, notamment l’organisation des Réunions de Concertation Pluridisciplinaires, les projets PNDS et le suivi des parcours de soins pour les maladies rares vasculaires du cerveau et de l’œil. Elle assure également le lien avec la plateforme d’expertise Paris Nord, la filière BRAIN-TEAM et le réseau européen VASCERN pour renforcer les synergies et favoriser l’innovation au bénéfice des patients.

Passionnée par la transmission et l’accessibilité de l’information en santé, elle contribue activement à la visibilité du CERVCO, notamment via son site internet, en veillant à rendre les contenus clairs et accessibles à tous les publics concernés (patients, professionnels de santé, associations).

D’abord secrétaire dans le secteur privé dés 1986, Solange Hello a intégré l’équipe du Service de Neurologie de l’hôpital Lariboisière en 2001. Elle a initialement exercé les fonctions de secrétaire de recherche et s’est investie dans le suivi de Projets Hospitaliers de Recherche Clinique concernant les maladies vasculaires cérébrales rares. Elle assure la fonction de secrétaire pour le CERVCO depuis le 1er janvier 2007.

Après l’obtention d’un doctorat en chimie de l’Université Claude Bernard Lyon I en 2005 et quelques années de recherche fondamentale Abbas Taleb a suivi une formation d’Attaché de Recherche Clinique (ARC) à l’institut Leonard De Vinci à Paris en 2010. Au décours de cette formation, il a intégré l’équipe du CERVCO et exerce actuellement la fonction de coordinateur d’essais cliniques. Il est responsable du recueil de données concernant les cohortes maladies rares.

Fanny Fernandes est docteur en Neurosciences. Après 15 ans de recherche préclinique en neurobiologie, sur les processus de myélinisation et de développement des glioblastomes, elle s’est tournée vers la recherche clinique en suivant les enseignements du DIU FIEC. Elle a ensuite animé le réseau national de recherche clinique FCRIN CRI-IMIDIATE sur les maladies auto-inflammatoires et auto-immunes puis le FHU ADAPT autour du développement de la médecine personnalisée en psychiatrie. Au sein du CERVCO elle anime le programme de recherche RHU Trt_cSVD qui a pour objectif de lutter contre les maladies des petits vaisseaux cérébraux en utilisant des approches pluridisciplinaires pour aboutir à des propositions innovantes pour la prise en charge des patients.

Diplômée d’un doctorat en pharmaco-oncologie, Estelle Dubus s’est d’abord intéressée à l’inhibition de l’angiogenèse dans les tumeurs pédiatriques comme cible thérapeutique et à la caractérisation des mécanismes de résistance associés. Au travers du programme de médecine personnalisée MAPPYACTS (#NCT02613962 ), elle a mis en place et coordonné un réseau national et européen de développement de modèles précliniques de tumeur pédiatrique en rechute. Après 15 ans en oncologie, elle a repris l’animation du DHU NeuroVasc et a structuré la recherche clinique au sein du département de neurologie. Aujourd’hui, chef de projet de la FHU NeuroVasc2030, elle anime le réseau neurovasculaire francilien dans le but de faire émerger de nouveaux projets : de la conception à la publication, coordination des équipes, animation des réseaux professionnels et veille au bon déroulement scientifique, réglementaire et budgétaire de chaque étape. Au sein du CERVCO, elle coordonne les essais cliniques et la remontée des données de file active, aide à la structuration des cohortes et bases de données, accompagne les collaborations et la réponse aux appels à projet.

Marie-Hélène De Sanctis est psychologue spécialisée en neuropsychologie au sein du service de Neurologie de l’Hôpital Lariboisière depuis 2017. Elle réalise des évaluations neuropsychologiques, anime des ateliers d’Éducation Thérapeutique du Patient et assure le suivi et le soutien psychologique des patients et de leurs proches. Elle intervient également au CERVCO pour l’évaluation neuropsychologique des patients atteints de maladies vasculaires rares du cerveau et de l’œil. Chargée de cours invitée à l’Université Paris 8, elle est également co-autrice d’une publication sur les manifestations insulaires en neuro-oncologie.

Sonia Reyes est psychologue à l’Assistance Publique. Elle a débuté son activité dans le Service de Neurologie du Pr. Bousser à l’hôpital Lariboisière et parallèlement au Centre de Neuropsychologie et du Langage dirigé par le Pr. Bruno Dubois à la Salpêtrière. Elle y a acquis une compétence particulière dans le dépistage de troubles cognitifs associés aux pathologies neurodégénératives et vasculaires du cerveau. Elle est actuellement psychologue au sein du département de neurologie de l’hôpital Lariboisière où elle prend en charge l’évaluation neuropsychologique des patients. Elle assure également la prise en charge psychologique de ces patients et de leur famille.

Au sein du CERVCO, elle assure l’évaluation neuropsychologique des patients, leur suivi, le soutien psychologique des patients et des familles. Enfin, elle participe des travaux de recherche clinique sur les troubles cognitifs au cours des pathologies neuro-vasculaires rares.

Aude Jabouley est psychologue à l’Assistance Publique depuis 9 ans. Elle a commencé à travailler en consultation mémoire dans les Hôpitaux Vaugirard-Gabriel Pallez et Paul Brousse. Elle y a acquis une compétence particulière dans le dépistage de troubles cognitifs associés aux pathologies neurodégénératives et vasculaires du cerveau. Depuis 7 ans et demi, elle est psychologue au sein du pôle « neuro sensoriel tête et cou » du Groupe Hospitalier Lariboisière-Fernand Widal où elle prend en charge l’évaluation neuropsychologique des patients. Elle assure également la prise en charge psychologique de ces patients et de leur famille.

Au sein du CERVCO, elle assure l’évaluation neuropsychologique des patients et leur suivi ainsi que le soutien psychologique des patients et des familles. Enfin, elle effectue actuellement des travaux de recherche clinique sur les troubles cognitifs au cours des pathologies neuro-vasculaires rares, en particulier la maladie de CADASIL.

Carla Machado est psychologue à l’Assistance Publique depuis 2012. Elle a commencé son activité clinique dans le service de Consultation Mémoire à l’hôpital Albert Chenevier où elle a développé une compétence dans l’évaluation des troubles cognitifs associés aux maladies neurodégénératives. Depuis, elle a rejoint l’équipe de psychologue dans le service de Neurologie du groupe hospitalier Lariboisière-Fernand Widal où elle prend en charge l’évaluation neuropsychologique des patients. Elle assure également la prise en charge psychologique de ces patients et de leur famille.

Au sein du CERVCO, elle assure les entretiens cliniques au sein des consultations multidisciplinaires pré symptomatique dans la maladie de CADASIL et participe aux consultations neurologiques dans le cadre de la remise des résultats génétiques. Elle participe également à des protocoles de recherche clinique sur les maladies neuro-vasculaires rares et est responsable du programme d’éducation thérapeutique du patient (ETP) pour l’angiopathie de moyamoya.

Le Professeur Homa Adle-Biassette est Chef du Service d’Anatomie et de Cytologie pathologique. Elle est Professeur d’Anatomie Pathologique. Elle est également membre de l’équipe INSERM 1141. Son intérêt principal est la neuropathologie et plus particulièrement le développement du système nerveux central. Elle a publié plus de 100 articles scientifiques dans le domaine de la neuropathologie.

Le Docteur Valérie Krivosic est ophtalmologiste, spécialisée dans les pathologies médicales et chirurgicales de la rétine. Après avoir réalisé un DEA dans l’unité INSERM dirigée par le professeur Tournier-Lasserve à l’université Paris VII, elle a été chef de clinique dans le service d’ophtalmologie dirigé par le professeur Gaudric à l’hôpital Lariboisière à Paris pendant 3 ans. Elle a ainsi acquis une compétence dans les pathologies de la vascularisation rétinienne tant sur le plan chirurgical (pour la rétinopathie diabétique par exemple) que sur le plan médical. Elle exerce actuellement son activité professionnelle à plein-temps à l’hôpital Lariboisière où elle se consacre à une activité chirurgicale et de recherche clinique sur les nouveaux médicaments de la rétine. Dans le cadre du CERVCO, elle prend en charge plusieurs affections des petits vaisseaux rétiniens telles que la vitréorétinopathie exsudative familiale, les télangiectasies maculaires idiopathiques ou la maladie de Von Hippel Lindau.

Ancien interne des hôpitaux de Paris, François NATAF a ensuite exercé la fonction de Chef de Clinique-Assistant des Hôpitaux puis de praticien hospitalier dans le service de neurochirurgie à l’hôpital Sainte-Anne à Paris de 1997 à 2022. Depuis 2022 il est praticien hospitalier dans le service de Neurochirurgie à l’hôpital Lariboisière à Paris.

Durant cette période, il a contribué au démarrage sur Paris et en France de l’activité de radiochirurgie, initialement et principalement sur les malformations artério-veineuses cérébrales. Il poursuit cette activité associée également à une activité chirurgicale au bloc opératoire.

Un équipement de radiochirurgie de dernière génération (ZAP-X) est en cours d’installation sur le site de l’hôpital Lariboisière. L’activité de radiochirurgie est une UF du service de Neurochirurgie de Lariboisière, sous la direction du Pr Hennequin, radiothérapeute à Saint-Louis. Cet équipement est l’aboutissement d’un projet du GHU Nord associant 7 services dans 3 hôpitaux (Lariboisière, Saint-Louis, Beaujon) en collaboration avec l’Institut de Radiothérapie Hartmann (dans le cadre d’un GCS). L’organisation médicale du GCS intègrera un conseil scientifique.

François NATAF est l’actuel Directeur médical du GCS de radiochirurgie. Les travaux en cours portent notamment sur la radiochirurgie des malformations vasculaires cérébrales (MAV et cavernomes).

Ancien interne des hôpitaux de Paris, le Docteur Anne-Laure Bernat est praticien hospitalier dans le service de Neurochirurgie de l’hôpital Lariboisière. Elle a réalisé un fellowship Clinique à Toronto au Canada. Au sein du département de neurochirurgie, elle prend en charge plus spécifiquement les maladies vasculaires neurochirurgicales, les méningiomes et les adénomes hypophysaires. Son activité de recherche scientifique en collaboration avec les équipes médicales intéressées porte essentiellement sur les maladies vasculaires neurochirurgicales et la gestion des patients victimes d’hémorragie méningée anévrismale. Dans le cadre du CERVCO, elle prend en charge les patients atteints d’anévrismes intra-crâniens, de malformations artério-veineuses et d’angiopathie de MOYA MOYA.

Le Professeur Sébastien Froelich est chef du service de Neurochirurgie de l’Hôpital Lariboisière. Ses travaux de recherche concernent plus particulièrement les affections de la base du crâne et certaines tumeurs comme le chordome. Dans le cadre du CERVCO, il prend plus particulièrement en charge les patients atteints de cavernomes cérébraux et d’angiopathie de moyamoya.

Ancien interne des hôpitaux de Paris et chef de clinique-assistant, Caroline Roos est neurologue, praticien hospitalier temps plein et responsable du Centre d’Urgences des Céphalées de l’hôpital Lariboisière. Elle s’est spécialisée dans la prise en charge des patients souffrant de céphalées primaires et secondaires Elle a participé à de nombreux travaux de recherche et fait partie du comité pédagogique du diplôme Inter-Universitaire Migraine et Céphalées. Dans le cadre du CERVCO, elle prend en charge les patients atteints d’ataxie épisodique et de migraine hémiplégique familiale ou sporadique. Elle est aussi référente pour la prise en charge des patients suivis dans le cadre du CERVCO, souffrant de céphalée.

Le Dr Vittorio Civelli est neuroradiologue interventionnel. Après une formation médicale et spécialisée à Milan (Italie) et un clinicat à l’hôpital Foch (Surennes) et à l’hôpital Lariboisière, il occupe depuis 2016 un poste permanent de Praticien Hospitalier dans le service de neuroradiologie interventionnelle dirigé par le Pr HOUDART où il se consacre à la prise en charge des pathologies vasculaires cérébrales et médullaires (anévrismes, fistules artério-veineuses, AVC, MAV), à la sclérose percutanée des angiomes et des anomalies vasculaires superficielles avec un intérêt clinique et de recherche principalement consacré au traitement de la pathologie sténosante veino-durale (traitement endovasculaire de l’acouphène pulsatiles et de l’hypertension intra-crânienne dite idiopathique), de l’hypotension du LCR, de la maladie de Moya-Moya et des malformations vasculaires superficielles.

Depuis 2014, le Dr Marc-Antoine Labeyrie est praticien hospitalier temps plein au sein du DMU neurosciences à l’hôpital Lariboisière. Il exerce la neuroradiologie interventionnelle et est spécialisé dans la prise en charge des pathologies artérielles et veineuses macrovasculaires de la tête, du cou et du rachis.

Au sein du CERVCO, il participe plus particulièrement aux RCP sur la maladie de Moyamoya et travaille sur le développement de nouvelles variables de phénotypage angiographique de cette maladie.

Ses autres thématiques de recherche sont : 1/ l’évaluation des techniques endovasculaires intracrâniennes innovantes (angioplastie de vasospasme, thrombectomie à la phase aigüe des AVC ischémiques, stenting des sinus latéraux dans l’hypertension intracrânienne idiopathique) ; 2/ L’épidémiologie des causes macrovasculaires rares d’ischémie cérébrale (carotid web, dissections artérielles cervicales et intracrâniennes) ; 3/ L’imagerie cérébrale quantitative (segmentation automatique de l’imagerie cérébrale à la phase aigüe des hémorragies sous arachnoïdiennes).

Professeur des Universités – Praticien Hospitalier, responsable de l’unité de Neuroradiologie Interventionnelle du Service de Neuroradiologie depuis 1997. Cette unité effectue annuellement 800 artériographies cérébrales et 500 interventions endovasculaires de la sphère cérébrale, ORL et médullaire par année. Il s’agit d’un des centres français ayant l’activité la plus importante dans ce domaine. L’activité clinique est supportée par une activité de recherche centrée sur l’évaluation des nouvelles techniques de traitement des anévrysmes intracrâniens, des malformations artério-veineuses cérébrales et de l’athérome des artères cérébrales.

Ancien Interne des hôpitaux de Paris, il a été Assistant Hospitalier Universitaire dans le service de Neurologie de l’hôpital Bichat et Chef de Clinique-Assistant dans le service de Neuroradiologie de l’hôpital Lariboisière. Il est Professeur de Neurologie à l’Université Denis Diderot depuis 2013, membre de l’Unité INSERM 1148 (Laboratory of Vascular Translational Science) et chef du département de Neurologie de l’hôpital Lariboisière. Il partage ses activités de soins entre la neurologie et la neuroradiologie interventionnelle pour la prise en charge des accidents vasculaires cérébraux et notamment des malformations vasculaires cérébrales. Ses travaux de recherche sont centrés sur le développement et l’évaluation de nouveaux traitements à la phase aigüe de l’accident vasculaire cérébral. Pr Mazighi est aussi dans la gouvernance de la FHU Neurovasc 2030, leader du work package 0.

Après un DES de Neurologie à Paris, Isabelle Crassard a effectué un clinicat à l’hôpital Lariboisière (Services de Neurologie et d’Angiohématologie). Elle est actuellement praticien hospitalier dans le département de neurologie de l’hôpital Lariboisière. Elle s’intéresse en particulier aux troubles de la coagulation à l’origine de certains accidents vasculaires cérébraux et aux maladies veineuses cérébrales. Dans le cadre du Centre Maladies Rares, elle prend plus particulièrement en charge les patients ayant une thrombose veineuse cérébrale.

Eric Jouvent est ancien interne et ancien Chef de Clinique – Assistant des hôpitaux de Paris. Il est Professeur des Universités en neurologie à l’Université Paris Diderot et Praticien Hospitalier dans le service de neurologie de l’hôpital Lariboisière. Il s’intéresse à la pathologie vasculaire cérébrale, notamment aux aspects cognitifs et comportementaux des maladies des petites artères cérébrales dont CADASIL.

Ses travaux de recherche portent sur les liens entre l’imagerie et les aspects cliniques dans les maladies des petites artères cérébrales et dans CADASIL, et en particulier sur le rôle du cortex cérébral.

Membre du comité exécutif de la FHU Neurovas2030, Pr Jouvent a un intérêt pour l’innovation et les nouvelles technologies en particulier autour de l’imagerie cérébrale.

Le Docteur Stéphanie Guey, Neurologue, ancien interne des Hôpitaux de Paris et titulaire d’une thèse de sciences en Génétique, est depuis septembre 2022 Maître de Conférences des Universités – Praticien Hospitalier (MCU-PH) au sein du centre de neurologie translationnel (CNVT) Lariboisière et de l’Université Paris Cité.

Au sein du CERVCO, (centre de référence dédié aux maladies vasculaires rares du cerveau et de l’œil), elle consacre son activité clinique et de recherche aux affections cérébrovasculaires rares de l’adulte et plus particulièrement les cavernomatoses cérébrales et les maladies vasculaires cérébrales d’origine génétique, en particulier celles liées aux anomalies des gènes COL4A1 et COL4A2.

Dr Guey a développé une expertise reconnue dans le diagnostic, la compréhension et le suivi de ces pathologies encore peu connues. Elle s’attache à améliorer le parcours de soins des patients et à favoriser le dialogue entre la recherche, les équipes médicales et les familles.

Membre du Conseil scientifique de l’Association COL4A1-A2, Dr Guey est engagée dans une collaboration étroite avec les représentants des patients pour favoriser la diffusion des connaissances, accompagner les familles et faire progresser la recherche dans une approche humaine et collective.

Le Professeur Dominique HERVE a initialement exercé la fonction de Chef de Clinique – Assistant des Hôpitaux au sein du service de neurologie vasculaire de l’hôpital Lariboisière dédiée à la prise en charge en phase aigüe des pathologies vasculaires cérébrales. Depuis Novembre 2006, Dominique HERVE est Praticien Hospitalier temps plein à Lariboisière et son activité clinique est centrée sur la prise en charge des maladies cérébrovasculaires rares. Il est Professeur Associé de Neurologie à l’Université Paris Cité depuis septembre 2025.

Au sein du Centre Neuro-Vasculaire Translationnel (CNVT) de l’hôpital Lariboisière, il est le responsable médical du Centre de Référence des maladies Vasculaires rares du Cerveau et de l’Oeil (CERVCO). Sa mission est pleinement dédiée au développement de ce centre de référence. Dans le cadre du CERVCO, son activité clinique et de recherche concerne principalement l’angiopathie de Moyamoya et les maladies génétiques des petites artères cérébrales (CADASIL et autres leucoencéphalopathies vasculaires génétiques). Il a récemment coordonné la rédaction de recommandations européennes concernant la prise en charge de l’angiopathie de Moyamoya sous l’égide de l’European Stroke Organisation (ESO). Il prend également en charge les patients atteints de cavernomatoses cérébrales et de forme familiale d’anévrysmes cérébraux.

Depuis 2022, il coordonne un groupe de travail européen dédié aux maladies cérébrovasculaires rares (NEUROVASC) au sein du réseau européen de référence pour les maladies vasculaires rares (VASCERN).

Le Professeur Hugues Chabriat est coordonnateur du centre de référence pour les maladies vasculaires rares du cerveau et de l’oeil (CERVCO). Ancien interne des hopitaux d’Ile de France (Cochin Port-Royal) et chef de clinique à la faculté de médecine de Saint-Antoine à Paris, il est professeur de neurologie à l’Université Denis Diderot (Paris VII), chef de service du Centre Neuro-vasculaire Translationnel (CNVT) à l’Hôpital Lariboisiere et co-responsable d’une équipe de recherche au sein de l’unité INSERM U1141.

Ses travaux de recherche concernent plus particulièrement les affections vasculaires rares des petits vaisseaux du cerveau, l’imagerie cérébrale des maladies artériolaires cérébrales et les troubles cognitifs d’origine vasculaire. Il participe avec l’équipe de génétique à l’étude de nouvelles familles de leucoencéphalopathies vasculaire dont l’origine reste à déterminer. Il développe avec d’autres chercheurs les outils d’imagerie pour évaluer, en particulier, l’évolution et les futures thérapeutiques de ces affections.

Il a publié plus d’une centaine d’articles ou de chapitres de livre consacrées aux leucoencéphalopathies vasculaires, à l’imagerie cérébrale des maladies des petits vaisseaux du cerveau et à CADASIL.